1. Introduction

Near-death experiences (NDEs), mystical experiences, and psychedelic drug experiences represent intriguing facets of human consciousness that have captivated researchers and spiritual seekers alike. While they arise from distinct contexts and triggers, there exists a remarkable overlap in the subjective accounts and transformative effects reported by individuals who undergo these phenomena. This convergence invites exploration into the profound similarities that underscore these seemingly disparate states of consciousness. By delving into their shared themes of transcendence, altered perception, and profound insights into existence, we can uncover the interconnected nature of human consciousness and the mysteries that lie beyond conventional understanding.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Kenneth Ring, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of Connecticut. His official website is www.kenringblog.com. Reprint requests should be addressed to Dr. Ring.

ABOUT THE JOURNAL: The Journal of Near-Death Studies from the International Association for Near-Death Studies (IANDS.org) is the only peer-reviewed scholarly journal devoted exclusively to the field of the study of near-death experiences (NDEs). To access the latest issues from the previous three years and receive new issues of the quarterly journal, you must subscribe to the journal simply by joining and becoming a member of IANDS. The Journal of Near-Death Studies also encourages submission of articles. Basic information about the journal is available.

ABOUT IANDS: Your IANDS membership helps provide the financial support for IANDS to pursue their mission of encouraging independent research into NDEs and educating the world about near-death and similar experiences — and their effects and implications. In return, IANDS will give you special access to members-only sections of their website including the Index to the Periodical NDE Literature from 1877 through 2011, their Vital Signs newsletter, annual IANDS conference and educational offerings. Other important links to IANDS include: NDE Accounts – NDE Archives – Store – Support – Publications – Brochures – Facebook – Twitter – YouTube.

The following is a reprint of the article “Paradise is Paradise: Reflections on Psychedelic Drugs, Mystical Experience and the NDE” published in the Journal of Near-Death Studies, 6(3) Spring 1988, Human Sciences Press.

2. Paradise is Paradise: Reflections on Psychedelic Drugs, Mystical Experience and the NDE

By Kenneth Ring, Ph.D.

Not long ago, I invited students in one of my undergraduate courses to participate in a simple experiment. “I’m going to mention a word,” I said, “and I want you to write down a number from -5 to + 5 in response to that word. The number you choose should reflect your gut feeling about this word. If you feel favorable toward it, choose some positive integer; if you feel unfavorable, choose a negative integer; if you feel neutral, use zero.” I paused, then said, “The word is ‘drugs.'”

Not surprisingly, the ratings my students provided me with were preponderantly negative, many quite so. This was the case despite the fact that the course I was teaching dealt with such topics as altered states of consciousness, near-death experiences (NDEs), and Eastern philosophies, and, as such, might be expected to attract students who would be more open to drug experimentation than most. Nevertheless, these students, as a whole, had strong negative associations to drugs.

I undertook this little exercise to sensitize the students to their existing attitudes that might serve as an emotional filter to screen out information about the apparent therapeutic value of using psychedelic drugs with the dying. The point of my relating this story here, however, is a more general one: when we read the word “drugs” most of us hear an alarm go off inside us that translates somewhere in the range between “caution” and “danger.”

For those of us who are said to be in “our middle years,” our alarm bell may be triggered by associations to the psychedelic counter-culture of the ’60s with its sensationalism, hysteria and ultimate self-destructiveness. But no matter what age we are, we hardly lack contemporary reminders to set off our warning bells. A few years ago, for example, the specter of junkies stalking the streets of our major cities in search of victims to assault and rob was frequently suggested in our media and political oratory. These days, it is more likely to be the latest sports scandal involving the use of cocaine by professional athletes or perhaps a news item reporting Nancy Reagan’s efforts to prevent drug abuse. In any event, the message comes to us in a thousand ways and can be expressed through the simple declaration (with minor variants): drugs are bad (evil, immoral, etc.).

I am not denying that many drugs are justifiably so condemned. Heroin is unquestionably a menace to its users and society; cocaine, in my view, is likewise a vicious and dangerous substance and its apparent increasing abuse in America is certifiably a cause for grave concern today. There is little controversy about these points among informed people.

My point, however, is quite different. It is merely to remind us that because most of us have internalized this well-conditioned prejudice against drugs, it may cause us to react with knee-jerk sympathy to any thesis demanding that we dismiss the proposition that drugs can provide us with experiences of the deepest value. And in this respect, nothing raises our hackles more stiffly than the suggestion that psychedelic drugs can induce a genuine mystical or religious experience.

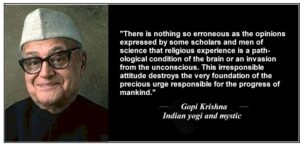

The stimulus for these reflections is a commentary on “the artificial paradise” of drugs that appeared in the Winter 1985 issue of Vital Signs (Maroder, 1985). In that piece, Maria Maroder quoted a lengthy excerpt from one of Gopi Krishna‘s books in support of her contention that truly enlightened people take strong exception to the claim that psychedelic drugs can engender an ecstatic vision comparable in phenomenology and effects to the mystical experience or the NDE.

Now, of course, the late Gopi Krishna was a highly respected sage and mystic whose many books leave no doubt about the authenticity of his own experiences of higher consciousness. Therefore, his opinions on this matter can hardly be brushed aside; rather, they merit the most serious consideration. Indeed, in my own work, especially Heading Toward Omega (1984), I have drawn quite extensively on Gopi Krishna’s writings and have cited him repeatedly in connection with my hypothesis that the NDE is an evolutionary catalyst in humanity’s ascent toward higher consciousness. I mention this only to make it clear that I, too, like many others, esteem the work and views of “the sage of Srinagar.”

Nevertheless, it is well known that the subject that Gopi Krishna addresses and has such decided opinions about has a considerable and turbulent history. This is only a relatively recent pronouncement, then, on a matter that scholars and mystics have been quarreling about for better than thirty years. Ever since Aldous Huxley brought this question into prominence with his ground-breaking book The Doors of Perception (1954), which really heralded the dawning of the modern psychedelic movement, the battle has been on over whether psychedelic drugs can be said to induce full-blown mystical experiences. Robert Zaehner (1957), for example, in a famous rebuttal to Huxley, protested vigorously against the latter’s claim that mescaline could effect a genuine mystical experience and felt that he had refuted Huxley’s argument, apparently largely on the basis of Zaehner’s own reaction to the drug. All that proved, however, is what everyone would surely concede: that psychedelic drugs do not invariably induce mystical experiences. Thus, the issue was soon joined and, ever since, a distinguished collection of experts has continued to provide authoritative pronouncements from both sides of the aisle. At the present time, it seems that one can only say that reasonable and informed persons, scholars and mystics alike, and some who can claim status in both worlds, remain at antipodes in this debate. There is no consensus on it, and it is misleading to imply that there is.

That said, it might be useful to sample briefly just a few opinions in order to consider some of the evidence and arguments that lead to conclusions opposed to those of Gopi Krishna.

An instructive case in point here is that of Alan Watts, the late comparative philosopher (he died in 1973) and author of about two dozen books on religion and Eastern thought. Like Zaehner, Watts was initially disinclined to equate psychedelic experiences with mystical states of consciousness. Like Zaehner again, Watts’s approach to the issue was personal (in his case, however, he ingested LSD). The chief difference between these two “inner” empiricists was that Watts did not limit his personal investigations to a single trial; he persevered with unexpected consequences. In his own words:

“All in all my first experience was aesthetic rather than mystical, and then and there — which is, alas, rather characteristic of me-I made a tape for broadcast saying that I had looked into the phenomenon and found it most interesting, but hardly what I would call mystical. This tape was heard by two psychiatrists … who thought I should reconsider my views. After all, I had made only one experiment and there was something of an art to getting it really working. It was thus that [one of the psychiatrists] set me off on a series of experiments which I have recorded in The Joyous Cosmology, and in the course of which I was reluctantly compelled to admit that — at least in my own case LSD had brought me into an undeniably mystical state of consciousness.” (Watts, 1973, pp. 398-399)

Another authority whose writings on religion and personal aura of luminous sagacity leave little doubt about his own realization is Huston Smith, another comparative philosopher of religion. Smith considered the question of the religious/mystical import of psychedelics from a variety of perspectives, including the research evidence available at that time (1964). For example, he reviewed and was impressed by the findings of the classic Good Friday study conducted by Walter Pahnke at Harvard in 1963 (Pahnke, 1970). Pahnke administered psilocybin to ten theology students and professors who then listened over loud speakers to a Good Friday service being conducted elsewhere in the same building; control subjects received a placebo, nicotinic acid. Afterward, the written reports of all subjects were blindly coded according to the degree to which they reflected each of nine traits of mystical experience, according to a typology of mysticism proposed by the philosopher W. T. Stace. Smith quoted Pahnke’s conclusion that, after tests of statistical significance were performed, “those subjects who received psilocybin experienced phenomena which were indistinguishable from, if not identical with … the categories defined by our typology of mysticism” (Smith, 1964, p. 521). Although he admitted that psychedelic drugs do not always necessarily trigger such experiences, Smith’s own assessment of the evidence from several such studies led him to the conviction that “given the right set and setting, the drugs can induce religious experiences indistinguishable from experiences that occur spontaneously” (Smith, 1964, p. 520).

Finally, the same conclusions was reached by a researcher and therapist who is internationally renowned for his meticulous and thorough investigations of the effects of psychedelics, particularly LSD, on human consciousness. Stanislav Grof is a Czech-born psychoanalyst, now living in the United States, who helped to pioneer the use of psychedelics in therapy in the mid-fifties. Now the author of several highly regarded books in this field, Grof is widely considered the leading authority in the world today on the transcendental effects of psychedelic agents. In this regard, in reviewing the findings of his own extensive program of research – at the time, having spanned nearly two decades-Grof summed up his views this way:

“From the phenomenological point of view, it does not seem to be possible to distinguish the experiences in psychedelic sessions from similar experiences occurring under different circumstances, such as instances of so-called spontaneous mysticism, experiences induced by various spiritual practices, and phenomena induced by new laboratory techniques.” (Grof, 1972, p. 50)

More authorities could easily be cited here to reinforce these conclusions, but my aim is not to refute Gopi Krishna’s position. It is only to demonstrate that competent experts, personally familiar with the terrain of mystical experience, have found what they consider to be persuasive evidence to support opposing claims.

Another of Gopi Krishna’s arguments against the use of drugs is that the experiences they do elicit have no transformative value. Although this may well be so in some cases, it is quite premature to draw this conclusion. The fact is that there is almost no rigorous and systematic research on this question, although there is an abundance of clinical and impressionistic data (to be mentioned shortly) that suggest that psychedelic experiences may indeed contain the seeds of transformation and spiritual growth in many specific instances. Clearly, to undertake to gather the data necessary to address the issue in a definitive way would be extraordinarily difficult owing to a multiplicity of methodological snarls — to say nothing of the conditions that seriously restrict any meaningful psychedelic research these days. For these reasons, a reliable assessment of this matter in the near future is unlikely. Nevertheless, it is my own opinion – and one that I think would be shared by many professionals (and some mystics) familiar with psychedelics – that drugs like LSD have been helpful in promoting the spiritual development of quite a few individuals, including some persons of very high attainment. Along these lines, it would make a worthwhile project for someone to collect and evaluate personal testimony from such individuals about the role of psychedelic experiences in their lives. Although this would be no substitute for the research we really need, it might at least provide some suggestive findings that would bear on Gopi Krishna’s contention. In the meantime – aside from what data we have from clinical studies-the question about the transformative power of psychedelics remains unanswered.

A related point here is that our own modern generalized prejudices against drugs should not obscure the fact that the ancient, enduring, and widespread use of indigenous psychoactive plants in sacred contexts implies that for the people of many cultures psychedelic agents were (and are) regarded with deep reverence. Their use in healing, religious and initiatory ceremonies throughout the world is so well known that I need only to remind the reader of it here to suggest that our own views about the values of psychedelic drugs may be shamefully myopic (see, for example, Masters & Houston, 1966; and Grinspoon & Bakalar, 1979). The contemporary individualistic and recreational usage of semisynthetic drugs such as LSD in secularized Western society is a radical deviation from the time-honored communal and ritualized ingestion of organic substances among traditional peoples. It is no wonder, then, that stripped of its social context, this kind of usage may offend and cause us to dismiss out of hand the potential of psychedelic drugs for conferring psychological insight and promoting spiritual growth.

In our own society, nowhere is the inherent value of psychedelics better demonstrated than in its professional use in therapeutic settings. Quite apart from their capacity to foster mystical states of consciousness, psychedelics must be recognized for the important role they play as catalysts in psychotherapy. In this respect, it is well known that such drugs have been found extremely useful in the treatment of various psychiatric disorders, including otherwise refractory cases of psychosis, drug addiction, alcoholism and even some instances of childhood autism – and that is by no means an exhaustive list. The work of Stanislav Grof (e.g., 1975, 1985) alone is a model for what therapeutic effects can be achieved with LSD when patients are in the hands of a master therapist. Of course, there have been MANY talented therapists who have reported very positive outcomes associated with the use of psychedelics and accounts of their work are, for the most part, easily accessible (e.g., Grinspoon and Bakalar, 1979; Masters and Houston, 1966; Naranjo, 1973; Yensen, 1985, 1988; Adamson, 1985; Anonymous, 1985). Perusal of such references may prove to be quite a mind-changing shock for those whose familiarity with psychedelics comes primarily from popular or second-hand sources.

Finally, we come to the question of the similarity between psychedelic episodes and NDEs. In Maria Maroder’s commentary, she stated that both mystical visions and NDEs are quite unlike psychedelic experiences. However, since I have already claimed that in some cases, psychedelic experiences are indistinguishable from mystical states of consciousness, it should not come as any surprise that, occasionally, psychedelics can indeed induce experiences that are fully the equivalent of NDEs.

For example, though it is not the only such case of which I have heard, I have in my archives a detailed written account of an experience, induced by a combination of LSD and hashish, that reproduces all the essential features of an NDE. In addition, I have interviewed the man who furnished me this account and am convinced his experience was genuine. Because of space limitations, I cannot provide excerpts here (and they would have to be lengthy to make my case through this example), but I can assure the reader that if you did not know the context of this man’s experience, you would be absolutely convinced that you were reading an account of a classic, deep NDE.

Of course, this thesis about the similarity, if not the equivalence, between drug induced states and NDEs is not original with me. Ronald Siegel (1980) proposed this view long ago for LSD and more recently he and a colleague made a similar argument for hashish (Siegel and Hirschman, 1984). Scott Rogo (1984) has done likewise for ketamine. Perhaps the best known and most edifying instance of this proposition, however, is to be found in the work of Stanislav Grof and Joan Halifax (1977) with terminally ill cancer patients.

In that study, dying cancer patients who volunteered to participate were offered the opportunity to have one or more sessions – preceded by extensive preparation and counseling – in which they would receive an administration of LSD or DPT. The primary therapeutic objective of this research was to provide dying patients with, in effect, a functional equivalent of an NDE before they died. It was hoped that by doing so, patients would be able more easily to come to terms with their own impending death, to resolve unfinished business with family members, and to live more fully until they died. In general, these results were found for the majority of the patients.

Our interest in this work, however, lies chiefly in assessing the extent to which LSD and DPT did actually facilitate NDE-like states of consciousness. Grof and Halifax’s data on this point show clearly that while psychedelic experiences are of course variable, in many instances the typical features of NDEs were evoked. Their case history material is replete with examples of out-of-body experiences, life reviews, experiences of profound peace, perceptions of golden light, encounters with deceased loved ones, telepathic communications, feeling oneself to be in the presence of God, etc. – in short, many of the features we have come to associate with the NDE.

And there is even more evidence that these experiences were the functional equivalent of NDEs. As I have argued in Heading Toward Omega (1984) — and as Maria Maroder also emphasized in her article the authenticity of a transcendental experience is revealed by its transformative effects. Therefore, if these psychedelically activated experiences are genuine, they should lead to changes similar to those reported by NDErs. In this connection, one quotation from Grof and Halifax will have to suffice to suggest that precisely this was the case:

“The striking changes in the subject’s hierarchy of life values observed after psychedelic sessions … [included the following] … Psychological acceptance of impermanence and death results in a realization of the absurdity and futility of exaggerated ambitions, attachment to money, status, fame, and power, or pursuit of other temporal values. … Time orientation is typically transformed; the past and future become less important as compared with the present moment. Psychological emphasis tends to shift from trajectories of large time periods to living “one day at a time.” This is associated with an increased ability to enjoy life and to derive pleasure from simple things. There is usually a distinct increase of interest in religious matters, involving spirituality of a universal nature rather than beliefs related to any specific church affiliation. On the other hand, there were many instances where a dying individual’s traditional beliefs were deepened and illumined with new dimensions of meaning.” (Grof & Halifax, 1977, pp. 127-128)

Such statements sound unmistakably like what we hear from NDErs.

The similarities between this kind of psychedelic experience and the NDE – as well as the former’s value in providing a rehearsal for death – is even further attested to by the statements furnished by those persons who have undergone both kinds of experience and who therefore can speak directly of their parallels. On this point, it is again worthwhile to quote Grof and Halifax:

“On several occasions patients who had psychedelic sessions later experienced brief episodes of deep agony and coma, or even clinical death, and were resuscitated. They not only described definite parallels between the experience of actual dying and their LSD sessions, but reported that the lesson in letting go and leaving their bodies, which they had learned under the influence of LSD, proved invaluable in this situation and made the experience much more tolerable. .. [For example, one of their patients, Ted] found the experience of actual dying extremely similar to his psychedelic experiences and considered the latter excellent training and preparation. “Without the sessions I would have been scared by what was happening, but knowing these states, I was not afraid at all” [he said].” (Grof & Halifax, 1977, pp. 59, 181-182)

Now, if we try to bring together the various strands of thought and evidence we have so far considered concerning mystical, psychedelic and near-death experiences, they would seem to coalesce around one conclusion: Paradise is paradise, however it is gained. There is inside each of us a radiant spiritual core that may remain dormant until some powerful catalyst occurs to arouse it. My reading of the evidence suggests that whether the trigger be a spontaneous mystical experience, a psychedelic episode, or an NDE, once this core is activated, it begins to unfold and bring about transformation in much the same way, as if an archetype of transformation were engaged (see especially Grosso, 1983, on this point).

Recently, I was delighted to read that Stanislav Grof, on the basis of his own 30 years of working with psychedelic and other radical forms of psychotherapy, has come to exactly the same conclusion, so I will use his words here to sum up my own views:

“According to the new data, spirituality is an intrinsic part of the psyche that emerges quite spontaneously when the process of self-exploration reaches sufficient depth. Direct experiential confrontation with the [deep] levels of the unconscious is always associated with a spontaneous awakening of a spirituality that is quite independent of the individual’s childhood experiences, religious programming, church affiliation, and even cultural and racial background. The individual who connects with these levels of his or her psyche automatically develops a new world view within which spirituality represents a natural, essential and absolutely vital element of existence.” (Grof, 1985, p. 368)

Having taken issue with several of the statements regarding psychedelic drugs in the Maroder article, let me end this one by joining with her in her final statement. At the conclusion of her piece, Maroder exhorts us to remember that the requirements of higher consciousness include self-discipline and that experience alone, however exalted, is not sufficient. Certainly I agree with her stricture and I think many who are familiar with the effects of psychedelic drugs, including some who are its strong proponents, would likewise concur. In this respect, individuals who may find themselves differing profoundly on the value of psychedelic drugs per se, and in their role in affording genuine mystical or religious experience, tend to agree that psychedelics do not in themselves constitute a spiritual path.

This point of view is explicitly endorsed by the well-known author Peter Matthiessen, whose interest gradually turned from psychedelic explorations to Zen Buddhism:

“I never saw drugs as a path, but for the next ten years, I used them regularly – mostly LSD but also mescaline and psilocybin. The journeys were all scaring, often beautiful, often grotesque, and here and there a blissful passage was attained that in my ignorance I took for religious experience…. I had bad trips, too, but they were rare; most were magic shows, mysterious, enthralling. After each — even the bad ones — I seemed to go more lightly on my way, leaving behind old residues of rage and pain. Whether joyful or dark, the drug vision can be astonishing, but eventually this vision will repeat itself, until even the magic show grows boring; for me, this occurred in the late 1960s, by which time D. [his wife] had already turned to Zen.

“Now those psychedelic years seem far away; I neither miss them or regret them. Drugs can clear away the past, enhance the present; toward the inner garden, they can only point the way. Lacking the temper of ascetic discipline, the drug vision remains a sort of dream that cannot be brought over into daily life. Old mists may be banished, that is true, but the alien chemical agent forms another mist, maintaining the separation of the “I” from true experience of the One.” (Matthiessen, 1978, pp. 44, 47-48)

Alan Watts‘s final appraisal of the value of LSD is almost identical:

“My retrospective attitude to LSD is that when one has received the message, one hangs up the phone. I think I have learned from it as much as I can, and, for my own sake, would not be sorry if I could never use it again. But it is not, I believe, generally known that very many of those who had constructive experiences with LSD, or other psychedelics, have turned from drugs to spiritual disciplines – abandoning their water wings and learning to swim. Without the catalytic experience of the drug they might never have come to this point, and thus my feeling about psychedelic chemicals, as about most other drugs (despite the vague sense of the word), is that they should serve as medicine rather than diet.” (Watts, 1973, p. 402)

And in the context of living a religious life, Huston Smith advocated the same position:

“No religion that fixes its faith primarily in substances that induce religious experiences can be expected to come to a good end. What promised to be a short cut will prove to be a short circuit; what began as a religion will end as a religion surrogate. Whether chemical substances can be helpful adjuncts to faith is another question. .. The conclusion to which evidence currently points would seem to be that chemicals can aid the religious life, but only where set within a context of faith (meaning by this the conviction that what they disclose is true) and discipline (meaning diligent exercise of the will in an attempt to work out the implications of the disclosures for the living of life in the everyday, common-sense world).” (Smith, 1964, pp. 529-530)

We are left, then, with the sense that although psychedelics in themselves cannot be used in lieu of a spiritual path, they can precipitate a spiritual awakening, akin to a mystical experience or NDE, which may lead an individual to pursue such a path. As such, psychedelic drugs may have a significant role to play in one’s spiritual life. Because of this, we should not be too quick to disdain or dismiss them as providing only a counterfeit spiritual experience or as having no value in accelerating the course of one’s spiritual transformation.

3. References

Adamson, S. (1985). Through the Gateway of the Heart. San Francisco, CA: Four Trees Publications.

Anonymous (1985). MDMA: A Multi-Disciplinary Investigation. Berkeley, CA: Earth Metabolic Design Laboratories.

Grinspoon, L., and Bakalar, J. (1979). Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Grof, S. (1972). Varieties of transpersonal experience. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 4, 45-80.

Grof, S. (1975). Realms of the Human Unconscious. New York, NY: Viking.

Grof, S. (1985). Beyond the Brain. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Grof, S., & Halifax, J. (1977). The Human Encounter With Death. New York, NY: Dutton.

Grosso, M. (1983). Jung, parapsychology, and the near-death experience. Anabiosis, 3, 3-38.

Huxley, A. (1954). The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Maroder, M. (1985). A comment on the artificial paradise. Vital Signs, 5(3), 14-15.

Masters, R., & Houston, J. (1966). The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience. New York, NY: Dell.

Matthiessen, P. (1978). The Snow Leopard. New York, NY: Bantam.

Naranjo, C. (1973). The Healing Journey. New York, NY: Ballantine.

Pahnke, W. (1970). Drugs and mysticism. In B. Aaronson & H. Osmond (Eds.), Psychedelics (pp. 145-165). Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Ring, K. (1984). Heading Toward Omega: In Search of the Meaning of the Near-Death Experience. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Rogo, D. S. (1984). Ketamine and the near-death experience. Anabiosis, 4, 87-96.

Siegel, R. (1980). The psychology of life after death. American Psychologist, 35, 911-931.

Siegel, R., & Hirschman, A. (1984). Hashish near-death experiences. Anabiosis, 4, 69-86.

Smith, H. (1964). Do drugs have religious import? Journal of Philosophy, 41, 517-530.

Watts, A. (1973). In My Own Way. New York, NY: Vintage.

Yensen, R. (1985). Toward a psychedelic medicine. Paper presented at the Second Annual Conference of the Association for the Responsible Use of Psychoactive Agents, Big Sur, CA, June 16-22.

Yensen, R. (1988). Helping at the edges of life: Perspectives of a psychedelic therapist. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 6.

Zaehner, R. (1957). Mysticism, Sacred and Profane. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.