This site uses affiliate links to Amazon.com Books for which IANDS can earn an affiliate commission if you click on those links and make purchases through them.

1. Introduction

Universal Salvation is the theological position that ALL people will be saved. This concept, present from the earliest days of Christianity, is supported by numerous verses in the Bible [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20], second in number only to those advocating Salvation by Good Works [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11]. Universalists do not reject the undeniable fact that Hell is in the Bible but contend that the function of Hell is for purification. Much later in the Christian story, when some claimed that Hell was a place for everlasting punishment, Universalists countered with their conviction that God was too good to condemn anyone to Eternal Hell! Today’s world news is saturated with the tragedies resulting from religions that insist on their own “exclusive” path to God, and Universalists are reasserting the relevance of that loving doctrine known to the earliest Christians — Salvation for ALL.

In this paper, I will attempt to make the following points clear:

a. For the first 500 years of Christianity, Christians and Christian theologians were broadly Universalist.

b. Translation/Mistranslation of the Scriptures from Greek to Latin contributed the reinterpretation of the nature of Hell.

c. Merging of Church and State fostered the corruption of Universalist thought.

d. Modern archeological findings and Biblical scholarship confirm Universalist thought among early Christians.

e. Contemporary Christian scholars find Universalist theology most authentic to Jesus.

To examine Universal Salvation during the first 500 years of Christianity, the works of three scholars are indisputably the finest: Hosea Ballou II’s Ancient History of Universalism (1842), Edward Beecher’s History of Opinions on the Scriptural Doctrine of Retribution (1878), and John Wesley Hanson’s Universalism, the Prevailing Doctrine of the Church for its First 500 Years (1899). I have used all these resources but have broadened Universalist history to include 20th Century discoveries and scholarship pertinent to Universalist Christianity.

2. In The Beginning

At its beginning, Christianity was a hopeful religion. In the words of St. Paul:

“There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male or female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

Communal meals, a culture of sharing and a tradition of helping others were the hallmarks of the early church. Despite a paternalistic culture, women were Apostles (Luke 8:2-3) and ministers (Romans 16:1).

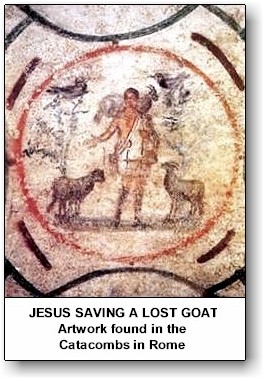

One of the best clues to early Christian theology is in artwork discovered at the Catacombs in Rome. Graves of common people were adorned with drawings of Jesus as the Good Shepherd — beardless and virtually indistinguishable from the Greco-Roman savior figure Orpheus. Other popular images there were the Last Supper and the Magi at the birth of Jesus. Occasionally in early Christian art, Jesus is shown working miracles using a magic wand! Significantly, the crucifix is noticeably absent from early art, as is any depiction of judgment scenes or Hell.

As we move into the middle of the 2nd Century, a shift takes place from writing works considered “Holy Scripture” to interpretations of it. The first writer on the theology on Christian Universalism whose works survive is St. Clement of Alexandria (150 – 215 CE). He was the head of the theology school at Alexandria which, until it closed at the end of the 4th Century, was a bastion of Universalist thought. His pupil, Origen (185 – 254 CE), wrote the first complete presentation of Christianity as a system, and Universalism was at its core. Origen was the first to produce a parallel Old Testament that included Hebrew, a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew, the Septuagint, and three other Greek translations. He was also the first to recognize that some parts of the Bible should be taken literally and others metaphorically. He wrote a defense of Christianity in response to a pagan writer’s denigration of it.

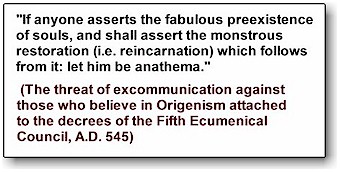

Prior to the Roman Catholic Church’s condemnation of all of Universalist thought in the 6th Century, Church authority had already reached back in time to pick out several of Origen’s ideas they deemed unacceptable. Some that found disfavor were his insistence that the Devil would be saved at the end of time, the pre-existence of human souls, the reincarnation of the wicked, and his claim that the purification of souls could go on for many eons. Finally, he was condemned by the Church because his concept of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit did not agree with the “official” Doctrine of the Trinity formulated a century after his death! After the 6th Century, much of his work was destroyed; fortunately, some of it survived.

According to Edward Beecher, a Congregationalist theologian, there were six theology schools in Christendom during its early years — four were Universalist (Alexandria, Caesarea, Antioch, and Edessa). One advocated annihilation (Ephesus) and one advocated Eternal Hell (the Latin Church of North Africa). Most of the Universalists throughout Christendom followed the teachings of Origen. Later, Theodore of Mopsuestia had a different theological basis for Universal Salvation, and his view continued in the break-away Church of the East (Nestorian) where his Universalist ideas still exist in its liturgy today.

3. “Harrowing of Hell” in Canon and Apocrypha

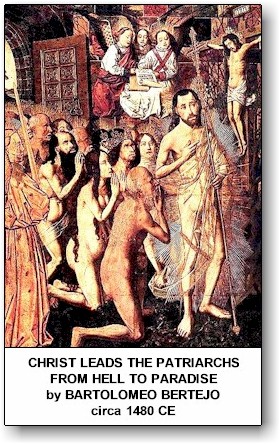

One of the primary beliefs of the early Christians was that Jesus descended into Sheol / Hades in order to preach to the dead and rescue all of those, as it clearly says in 1 Peter 3:20:

“… who in former times did not obey.” (1 Peter 3:20)

This terminology is familiar to anyone who has recited the Apostle’s Creed which states that Jesus descended to Hell after his death, before his resurrection. Known as the “Harrowing of Hell,” this is a major theme in Universalism because it underscores the early belief that judgment at the end of life is not final and that all souls can be saved after death. Interestingly, in the early Church there were not only prayers for the dead, but St. Paul notes there were also baptisms for the dead (1 Corinthians 15:29).

In later times, the church attempted to reinterpret the text to narrow the categories of people saved from Hell to the Jewish prophets and the righteous pagans. Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan take this approach in their latest book, The Last Week. (Curiously, they omit the key verse “those who in former times did not obey.”) However, in his earlier book, The Cross That Spoke, John Dominic Crossan is more favorable to the Universalist view. For example, he relates a story from the non-canonical Gospel of Peter in which two angels come down from Heaven to get Jesus out of the tomb on Easter morning. As they are carrying him out and are about to ascend to Heaven, a voice from Heaven asks them:

“Hast thou preached to them that sleep?” The wooden cross that is somehow following them out of the tomb speaks and says, “Yes!” (Gospel of Peter)

In discussing Jesus’ decent into Hell, Crossan also sites another classic Universalist text, 1 Peter 4:6 which says:

“For this is why the Gospel was preached even to the dead, that though they were judged in flesh like men they might live in the spirit like God.” (1 Peter 4:6)

He also notes that in Colossians 2:15, Jesus:

“… disarmed the principalities and powers and made a public example of them.” (Colossians 2:15)

and in Ephesians 4:8-9:

“Therefore it is said, ‘When he ascended on high, he made captivity itself a captive; he gave gifts to his people.’ (When it says, ‘He ascended,’ what does it mean but that he also descended into the lower parts of the earth? He who descended is the same one who ascended far above all heavens, so that he might fill all things.'”) (Ephesians 4:8-9)

Understanding the role of the “Harrowing of Hell” has been expanded by recent archeological findings and modern Biblical scholarship. Among the discoveries over the past 100 years is the Apocalypse of Peter, written about 135 C.E. (not to be confused with the Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter discovered at Nag Hammadi in 1947). For a time, it was considered for inclusion into the New Testament instead of the Revelation to John. It is referred to in the Muratorian Canon of the early Church, as well as in the writings of St. Clement of Alexandria. (It should be noted that the Universalist passage from the Apocalypse of Peter is found in the Ethiopian text but is not part of the fragment text found at Akhmim, Egypt.) In the Ethiopic copy, Peter asks Jesus to have pity on the people in Hell, and Jesus says they will eventually all be saved. Later, Peter (who is writing to Clement) says to keep that knowledge a secret so that foolish men may not see it. This same theme is repeated in the Second Book of the Sibylline Oracles in which the saved behold the sinners in Hell and ask that mercy be shown them. Here, the sinners are saved by the prayers of the righteous.

Another 2nd Century work, The Epistle of the Apostles, also states that our prayers for the dead can affect their forgiveness by God. The 2nd Century Odes of Solomon, which was discovered in the early 20th Century, was for a time considered to be Jewish, then Gnostic, and more recently, early Christian. Its theme is that Jesus saves the dead when they come to him in Hell and cry out:

“Son of God, have pity on us!” (Odes of Solomon)

In the 4th/6th Century Syriac Book of the Cave of Treasures, Jesus:

“… preached the resurrection to those who were lying in the dust” and “pardoned those who had sinned against the Law.” (Book of the Cave of Treasures)

In the Gospel of Nicodemus (a.k.a. Acts of Pilate), a 4th /5th Century apocryphal gospel, Jesus saves everyone in the Greek version but rescues only the righteous pre-Christians in the Latin translation. In What is Gnosticism?, Karen King identifies the Nag Hammadi Gospel of Truth as teaching Universal Salvation; she states that The Apocryphon of John (a.k.a. The Secret Book of John) declares all will be saved except apostates. In the Coptic Book of the Resurrection, all but Satan and his ministers are pardoned.

Interestingly, belief in the “Harrowing of Hell” has had some validation by modern day near-death experiencers (people who have been resuscitated following a period of clinical death). While most near-death experiencers report a “heavenly” experience of Light and overwhelming love, many of those whose experience begins in “hellish” turmoil and darkness say that their descent was reversed when they called out to God or Jesus.

4. The Church-State Conundrum

Many think that Christianity was at its best during its first 300 years — a time of immense diversity of opinion, creativity, and expectation. Although the official sanction of governments provided the Church with some very critical benefits (like not feeding Christians to lions!), some of the vitality of the young Church was inevitably compromised. Its legitimization in the 4th Century, first by the king of Armenia, then by Constantine of Rome, and finally by the king of Ethiopia, led to a new era for Christianity. Constantine, being a military man, wanted standardization in all things. The Emperor called the Council of Nicea because at the time, the Bishop of Rome was not yet Pope (in the way we think of him today). According to Roman Catholic scholar Jean-Guy Vaillancourt, the Pope did not become the head of the Roman Church until 752 CE. At that time, Charlemagne recognized the Bishop of Rome as the singular Pope, and Pope Leo III reciprocated by legitimizing Charlemagne as the Holy Roman Emperor. It should be noted that the 6th Century Emperor Justinian — NOT the Bishop of Rome — called the Church council where Universalism was condemned.

5. Jesus Seminar “Endorses” Christian Universalism

Of all modern Biblical scholars, none have gained so much publicity and been so readily accessible to the lay reader than a group called the Jesus Seminar. Over 150 Biblical scholars pooled their knowledge for the express purpose of analyzing the Gospels to determine which words and deeds were authentic to Jesus. Their resulting “Scholars’ Editions” of the Gospels were remarkable for the few passages that were thought to be original to Jesus. For Universalists, the most significant result of the Seminar’s scrutiny was their inadvertent highlighting of many Universalist passages. By far, verses advocating Universal Salvation received the most endorsement from the Jesus Seminar as authentic to Jesus. While they rejected some of the “zingers” (e.g., John 12:32), virtually all Jesus’ classic parables that have been interpreted as Universalist since the beginning of Christian theology were judged by the Jesus Seminar to be genuine to him, including: The Parable of the Lost Sheep (Matthew 18:12-13; Luke 15:4-6), The Workers in the Vineyard (Matthew 20:1-15), The Parable of the Lost Coin (Luke 15:8-9), and the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32). Also, the verses relating to the fact that Hell is not permanent and used only for rehabilitation/purification were determined authentic by the Jesus Seminar. They are: Settle with Your Opponent (Matthew 5:25-26; Luke 12:58-59) and the Parable of the Wicked Servant (Matthew 18:23-34). Finally, although it was mutilated in part by the Jesus Seminar scholars, Jesus’ teaching to be like God and love our enemies as God is good to the just and the unjust (Matthew 5:44-46) was voted genuine to Jesus.

It is noteworthy that the Seminar rejected all of the verses relating to the “Jesus Saves” theology as original to Jesus. John Calvin‘s Predestination fared only slightly better with only two verses seen as original to Jesus (Matthew 6:10, Matthew 10:29). Some classic sayings of Jesus on Good Works were deemed authentic, such as Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-35), Jesus on forgiveness (Matthew 6:12), and the Parable of the Sower (Mark 4:3-8; Matthew 13:3-8; Luke 8:5-8).

6. Mistranslations and Misanthropes

One of the essential tenants of Universalism is that all punishment in Hell is remedial, curative, and purifying. As long as Western Christianity was mainly Greek — the language of the New Testament — it was Universalist.

Interestingly, NONE of the Greek-speaking Universalists ever felt the need to explain Greek words such as “aion” and “aionion.” In Greek, an aion (in English, usually spelled “eon“) is an indefinite period of time, usually of long duration. When it was translated into Latin Vulgate, “aion” became “aeternam” which means “eternal.” These translation errors were the basis for much of what was written about Eternal Hell.

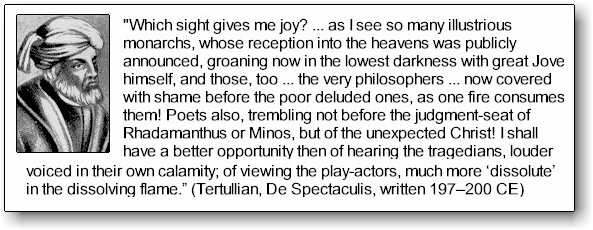

The first person to write about Eternal Hell was the Latin North African Tertullian who is considered the Father of the Latin Church. As most people reason, Hell is a place for people you don’t like to go! Tertullian fantasized that not only the wicked would be in Hell but also every philosopher and theologian who ever argued with him! He envisioned a time when he would look down from Heaven at those people in Hell and laugh with glee!

By far, the main person responsible for making Hell eternal in the Western Church was St. Augustine (354-430 CE). Augustine’s Christian mother did not kick him out of her house for not marrying the girlfriend he got pregnant, but she did oust him when he became a Manichean Gnostic. Later, he renounced Manichaeism and returned to the Roman Church where he was made Bishop of Hippo in North Africa. He did not know Greek, had tried to study it, but stated that he hated it. Sadly, it is his misunderstanding of Greek that cemented the concept of Eternal Hell in the Western Church. Augustine not only said that Hell was eternal for the wicked but also for anyone who wasn’t a Christian. So complete was his concept of God’s exclusion of non-Christians that he considered un-baptized babies as damned; when these babies died, Augustine softened slightly to declare that they would be sent to the “upper level” of Hell. Augustine is also the inventor the concept of “Hell Lite”, a.k.a. Purgatory, which he developed to accommodate some of the Universalist verses in the Bible. Augustine acknowledged the Universalists whom he called “tender-hearted,” and curiously, included them among the “orthodox.”

At this point, it should be noted that many in the early Church who were Universalist cautioned others to be careful whom they told about Universalism, as it might cause some of the weaker ones to sin. This has always been a criticism of Universalism by those who think that people will sin with abandon if there is no threat of eternal punishment. In fact, modern psychology has affirmed that love is a much more powerful motivator than fear, and knowing that God loves each and every person on the planet as much as God loves you does not promote delinquency. Conversely, it is Christian exclusivity that leads to the marginalization of other human beings and the thinking that war and cruelty to the “other” are justified since they’re going to Hell anyway! This kind of twisted thinking led to the persecution of the pagans, the witch hunts, the Inquisition, and the Holocaust.

7. Universalism in the East and Zoroastrian Roots

A slightly different type of Universalist theology was taught in the Aramaic speaking Church of the East (Nestorian). Virtually all of the Greek-speaking Universalists built on Origen’s system that emphasizes free will. Origen saw an endless round of purification and relapse, but that in the end, God’s love would draw all back to God. According to Dr. Beecher, Theodore of Mopsuestia (350-428 CE) saw:

“… sin as an unavoidable part of the development and education of man; that some carry it to a greater extent than others, but that God will finally overrule it for their final establishment in good.”

Theodore of Mopsuestia was known in the Nestorian Church as “The Interpreter.” The 5th Century with its ongoing feuding councils saw major splits in the Christian Church. The Coptic Church of Egypt and Ethiopia split in 451CE; the Armenian Church left about the same time; the Church of the East (Nestorian) left in 486 CE. At the time of the split, the Nestorian Church was larger in numbers than the Roman Church. It included the all of the Sasanian Persian Empire (which stretched from the Euphrates to India), along the Silk Road through modern Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, through Tibet, Mongolia, and into China. Additionally, it had established Christian churches in the south of India by the end of the 2nd Century. While it suffered under Moslem invasion in the 7th Century, it continued to grow in the Far East until being virtually annihilated by Tamerlane in the 14th Century. Today, only a quarter-million remain. The Nestorian Church continued to be Universalist for most of its history, and a Universalist liturgy written by Theodore of Mopsuestia is still in use today. Also, the Book of the Bee written in the 13th Century by Bishop Solomon of Basra includes the Universalist teachings of Isaac, Diodorus, and Theodore in Chapter 60. We know from Martin Palmer in the Jesus Sutras that the Nestorians who proselytized in China in the early days had only two Christian books: the Gospel of Matthew and an early Christian prayer book known as the Didache or The Teachings of the Twelve Apostles. The appeal of Christianity in the Far East was that Jesus could save you and take you to Paradise, avoiding the risk of an undesired reincarnation.

Christopher Buck notes in his article, “The Universality of the Church of the East: How Persian Was Persian Christianity?” (PDF) that the success of Christian conversions in the East may have been the affinity of Christianity with Zoroastrianism. Unlike Manichaeism and other Gnostic Christianity, Zoroastrianism (like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) maintains that the world was created good and was corrupted by evil. In Zoroastrianism, the basic tenants are:

God-Satan, Good-Evil, Light-Darkness, Angels-Demons, Death-Judgment, Heaven-Hell, and at the end of time, the resurrection of the body and life everlasting.

Zoroaster was a Universalist, as he says in his Hymns to God:

“If you understand these laws of happiness and pain which God has ordained, O Mortals, there is a long period of punishment for the wicked and reward for the pious, but thereafter eternal joy shall rein forever.” (Y 30:11 emphasis added).

In Zoroastrianism, while God is wholly good, there is no doctrine of forgiveness; your good deeds must always outnumber your bad deeds in order to avoid purification in Hell. Christianity brought Jesus’ message that God forgives sins for the asking! Also, one doesn’t need a priest as an intercessor or a sacrifice to obtain God’s grace. This affinity is best illustrated in a 13th Century Christmas liturgy of the Nestorian Church which states that:

“The Magi (Zoroastrian priests) came … they opened their treasures and offered him (Jesus) their offerings as they were commanded by their teacher Zoroaster who prophesized to them.”

What is implicit in the Gospel of Matthew is explicit in this Nestorian liturgy. Zoroaster had predicted the coming of future saviors “from the nations” (e.g., countries other than Persia). If you wanted to make converts in a Zoroastrian world, the story of the Magi at the birth of Jesus was your entree.

8. Universalism Officially Condemned in the West

Although the Roman Church had condemned some of Origen‘s other ideas, his Universalism was never questioned, nor were the writings of any other Universalist. There were even Universalists among the Gnostics; although Gnosticism had been condemned heartily by the Church, Universalism had never been listed among their errors. If Universal Salvation were heretical, how could the Church explain all those avowed Universalists who had already been made Saints (St. Clement of Alexandria, St. Macrina the Younger and her brother, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and others)? As mentioned earlier, it was the Emperor Justinian who initiated the deed.

Universalism had never been officially condemned prior to Justinian’s convening the Council of Constantinople in 553CE, but this momentous decision was made against a background of turmoil in the Church and Western civilization. Latin-speaking Christians in the Church began to overshadow the Greek-speakers, and the Nestorian Church of the East had recently split from the Catholic West. (In all fairness, the Latin Church was doing well to have anyone who could read Latin — much less Greek.) Less than eighty years earlier, the Western Roman Empire had fallen to pagan barbarians. The Roman Church had long before become the handmaiden of the State. What could be better for control in an age of superstition and fear than to make Hell eternal and Salvation possible only through the Church? Less than a century later, all of Christianity (Latin, Greek, Armenian, Coptic, as well as the Nestorian Church of the East) would be either partially or totally overrun by Moslem conquerors.

9. Conclusion

Compare the hopeful, positive art of the early Church in the Catacombs with the scenes of Hell and damnation on the wall of almost every Medieval Catholic Cathedral. These scenes were made even more terrifying by the Latin mistranslation of Jesus’ Parable of the Sheep and Goats (Matthew 25:31-46). In the West, Augustine trumped Origen, and what was an “eon” in the original Greek became “eternal” in Latin.

While Universalism continued in the Church of the East, in the West from the 6th Century forward, it was relegated to the realm of mystics until the Reformation when the idea of Universal Salvation was resurrected. Universalism continues today as a theological position among a fair number of Christians in a variety of denominations. It is ripe for revival.

10. References

Ballou, H. (1842). Ancient history of Universalism: From the time of the apostles to the Fifth General Council. Forgotten Books. (Original work published in 1878).

Beecher, E. (2007). History of opinions on the scriptural doctrine of retribution. Kessinger Publishing, LLC.

Borg, M. & Crossan. J.D. (2006). The last week: What the gospels really teach about Jesus’ final days in Jerusalem. HarperOne.

Buck, C. (1996). The universality of the Church of the East: How Persian was Persian Christianity? (PDF) Journal of the Assyrian Academic Society.

Crossan, J.D. (2008). The cross that spoke: The origins of the passion narrative. Wipf & Stock Pub.

Hanson, J.W. (2012). Universalism, the prevailing doctrine of the Church for its first 500 years with authorities and extracts. Forgotten Books. (Original work published in 1899).

King, K. (2005). What is Gnosticism? Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Miller, R. J. (1995). The complete gospels: Annotated scholar’s version. Polebridge Press.

Palmer, M. (2001). The Jesus sutras: Rediscovering the lost scrolls of Taoist Christianity. Wellspring/Ballantine.

Vaillancourt, J. (1980). Papal power: A study of Vatican control over lay Catholic Elites. Univ of California Pr.

Vincent, K. R. (2006). The salvation conspiracy: How hell became eternal. The Universalist Herald. Retrieved from: www.christianuniversalist.org