This site uses affiliate links to Amazon.com Books for which IANDS can earn an affiliate commission if you click on those links and make purchases through them.

1. About Kabbalah

Kabbalah (literally “receiving” in Hebrew) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought. Its definition varied according to the tradition from its religious origin as an integral part of Judaism, to its later Christian, New Age, and occult adaptions. Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between the unchanging, mysterious eternal God and the finite universe of God’s creation. Kabbalah seeks to define (1) the nature of the universe and the human being, (2) the nature and purpose of existence, and (3) various other ontological questions. Kabbalah presents methods to aid understanding of these concepts and to thereby attain spiritual realization.

2. A Brief Introduction to Kabbalah

Kabbalah originally developed entirely within the realm of Jewish thought and kabbalists often use classical Jewish sources to explain and demonstrate its esoteric teachings. These teachings are thus held by followers in Judaism to define the inner meaning of both the Hebrew Bible and traditional Rabbinic literature, their formerly concealed transmitted dimension, as well as to explain the significance of Jewish religious observances.

Traditional practitioners believe its earliest origins pre-date world religions, forming the primordial blueprint for Creation’s philosophies, religions, sciences, arts and political systems. Historically, Kabbalah emerged, after earlier forms of Jewish mysticism, in 12th- to 13th-century Southern France and Spain, becoming reinterpreted in the Jewish mystical renaissance of 16th-century Ottoman Palestine. It was popularized in the form of Hasidic Judaism from the 18th century onwards. 20th-century interest in Kabbalah has inspired cross-denominational Jewish renewal and contributed to wider non-Jewish contemporary spirituality, as well as engaging its flourishing emergence and historical re-emphasis through newly established academic investigation.

3. An Overview of the Kabbalah

Kabbalah is considered by its adherants as a necessary part of the study of Torah and as an inherent duty of observant Jews to follow. Kabbalah teaches doctrines which are accepted by some Jews as the true meaning of Judaism while other Jews have rejected these doctrines as heretical and antithetical to Judaism.

After Biblical Hebrew prophecy, the first documented schools of mysticism in Judaism are found in the 1st and 2nd centuries as described in the earliest book on Jewish mysticism called the Sefer Yetzirah. Their method for mystical experiences is known as “Merkabah mysticism” (i.e., contemplation of the Ezekiel‘s divine “chariot”) which lasted until the 10th century, where it was incorporated into the medieval emergence of the Kabbalah in Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries. Its teachings as embodied in the Zohar (a foundational text for kabbalistic thought) and became the foundation of later Jewish mysticism. Modern academic study of Jewish mysticism refers to the term “Kabbalah” as being the particular doctrines which emerged fully expressed in the Middle Ages, as distinct from the earlier Merkabah mystical concepts and methods. The “ecstatic tradition” of Jewish meditation strives to achieve a mystical union with God.

4. The History of Jewish Mysticism

According to the traditional understanding, Kabbalah dates to the days of Adam and Eve. It came down from a remote past as a revelation to elect righteous people and was preserved only by a privileged few. Talmudic Judaism records its view of the proper method for teaching Kabbalah wisdom. Ezekiel and Isaiah had prophetic visions of an angelic chariot and divine throne which later Kabbalah writings incorporated into to the Four Worlds. According to Kabbalists, the Kabbalah’s origin began with secrets which God revealed to Adam. According to the rabbinic Midrash, God created the universe through the Ten Sefirot. When read by later generations of Kabbalists, the Torah’s description of the creation in the Book of Genesis reveals mysteries about the godhead itself, the true nature of Adam and Eve, the Garden of Eden, the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and the Tree of Life, as well as the interaction of these supernal entities with the Serpent which leads to disaster when they eat the forbidden fruit, as recorded in Genesis 3. The Bible provides ample room for mystical interpretations: the prophet Ezekiel’s visions, Isaiah’s vision of the Temple in Isaiah (Chapter 6), Jacob’s vision of the ladder to heaven and Moses’ encounters with the Burning bush and God on Mount Sinai are evidence of mystical events in the Tanakh that form the origin of Jewish mystical beliefs.

Talmudic doctrine forbade the public teaching of esoteric doctrines and warned of their dangers. In the Mishnah (Hagigah 2:1), rabbis were warned to teach the mystical creation doctrines only to one student at a time. To highlight the danger, one Jewish legend called “The Four Who Entered Paradise” describes the outcome of four prominent rabbis of the Mishnaic period (1st century A.D.) who had visions of paradise: one rabbi looked and died, another rabbi looked and went insane, another rabbi destroyed his plants, and the last rabbi found peace and was fit to handle the study of mystical doctrines.

The mystical doctrines of Hekhalot (heavenly “chambers”) and Merkabah texts lasted from the 1st century B.C, through to the 10th century A.D. before giving way to the emergence of the Kabbalah. Initiates were said to “descend the chariot” – a possibly reference to meditating on the heavenly journey through the spiritual realms. Their goal was to arrive before the transcendent awe of God rather than entering into the divinity. From the 8th through the 11th centuries, Sefer Yetzirah and Hekhalot texts made their way into European Jewish circles. The Kabbalah’s medieval beginnings originated from mystical circles in 12th century France and 13th century Spain. Also in the 13th century a classic Rabbinic figure named Nachmanides helped Kabbalah gain mainstream acceptance through his Torah commentary. There were also certain elder sages of mystical Judaism who are known to have been experts in Kabbalah. One of them was Isaac the Blind (1160-1235) who is widely argued to have written the first work of classic Kabbalah, the Sefer Bahir, which laid the groundwork for the creation of the Sefer Zohar, written by Moses de Leon and his mystical circle at the end of the 13th century. One of the best known experts in Kabbalah was Nachmanides (1194-1270), a student of Isaac the Blind, and whose Torah commentary is considered to be based on the Kabbalah. Another expert was Bahya ben Asher (died 1340) who also combined Torah commentary and Kabbalah.

The Zohar was the first popular work of Kabbalah and the most influential. From the 13th century onward, Kabbalah began to be widely disseminated and branched out as extensive literature. In the 19th century, the historian Heinrich Graetz argued the emergence of Jewish esotericism at this time coincided with the rising influence of the philosophy of Maimonides. Scholars have argued that the impact of Maimonides can be seen in the change from orality to writing in the 13th century when Kabbalists began writing down many of their oral traditions in part as a response to the attempt of Maimonides to explain older esoteric subjects philosophically. However, many Orthodox Jews reject this idea of Kabbalah undergoing significant historical change. After the Zohar was published for public consumption in the 13th century, the term “Kabbalah” began to refer more specifically to teachings related to the Zohar. At an even later time, the term “Kabbalah” began to generally be applied to Zoharic teachings as elaborated upon by Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534-1572 A.D.). Historians generally date the start of Kabbalah as a major influence in Jewish thought and practice with the publication of the Zohar and climaxing with the spread of the Luria’s teachings. Luria’s disciples, Rabbi Hayim Vital and Rabbi Israel Sarug, both published Luria’s teachings which gained widespread popularity. Luria’s teachings came to rival the influence of the Zohar itself. Along with Moses de Leon, Rabbi Luria stands as the most influential mystic in Jewish history. In the 20th century, Yehuda Ashlag (1885-1954) of Palestine, was a leading esoteric kabbalist in the traditional mode, who translated the Zohar into Hebrew with a new approach in Lurianic kabbalah.

5. Hasidic Judaism

Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760) was the founder of Hasidism whose teachings were based on Lurianic kabbalah. The ecstatic fervour of early Hasidism developed from historical influences of Jewish mysticism, but sought a communal revival by centering Judaism around the central principle of “devekut” (i.e., mystically cleaving to God). For the first time, this new approach transformed kabbalistic theories for the elite into a popular social and mystical movement complete with its own doctrines, texts, teachings and customs. Rabbi Baal Shem Tov developed schools of Hasidic Judaism, each with different approaches and thought. Hasidism instituted a new concept of leadership in Jewish mysticism, where the elite scholars of mystical texts now took on a social role as embodiments and intercessors of divinity for the masses. With the 19th century consolidation of the movement, leadership became dynastic.

6. The Concealed and Revealed God

The nature of divinity prompted kabbalists to envision two aspects of God: (1) God in essence is absolutely transcendent, unknowable, limitless divine simplicity, and (2) God in manifestation – the revealed persona of God through which He creates and sustains and relates to humanity. Kabbalists believe these two aspects are not contradictory but complement one another. They are emanations revealing the concealed mystery from within the Godhead. The structure of these emanations of God have been characterized in various ways: Sefirot (Divine attributes) and Partzufim (Divine “faces”), Ohr (spiritual light and flow), Names of God and the supernal Torah, Olamot (Spiritual Worlds), a Divine Tree and Archetypal Man, Angelic Chariot and Palaces, male and female, enclothed layers of reality, inwardly holy vitality and external Kelipot shells, 613 channels (“limbs” of the King) and the Divine souls in man. Kabbalists see all aspects as unified through their absolute dependence on their source in the Infinte/Endless.

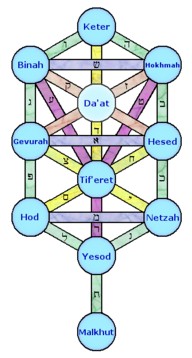

7. Sephirot and the Divine Feminine of Shekhinah

The Zohar elaborates upon the Sephirot – the ten emanations of God sustaining the universe – from its concealment from humanity to its revelation. These emanations are described as one light being poured into ten vessels. These Sephirot emanations are described metaphorically as manifestating in the form of the “Tree of Life and Knowledge” and its corresponding form: humanity as exemplified as Adam Kadmon. This metaphor allows humans to understand the Sephirot as corresponding to their soul’s psychological faculties and corresponding to the masculine and feminine aspects of God. As Genesis 1:27 states, “So God created mankind in His own image, in the image of God He created them; male and female He created them.” Corresponding to the last “sefirah” in Creation is the indwelling “shekhinah” (Feminine Divine Presence). The downward flow of divine Light in Creation forms the supernal Four Worlds: (1) Atziluth, (2) Beri’ah, (3) Yetzirah and (4) Assiah. The acts of human beings unite or divide the manifestation of these heavenly masculine and feminine aspects of the Sephirot. But once these manifestations become harmonized, God’s creation is complete. As the spiritual foundation of all Creation, the Sephirot corresponds to the Names of God in Judaism and the particular nature of any being.

8. The Ten Sefirot as the Process of Creation

According to Kabbalah cosmology, the Sefirot corresponds to various levels of creation. The ten Sefirot exists “fractally” within each of the Four Worlds. There are four worlds existing within each of the larger Four Worlds, each containing ten Sefirot which themselves and each containing ten Sefirot, to an infinite number of levels. The Sefirot are considered revelations of the Creator’s will and they should not be understood as ten different “gods” but as ten different ways the one God reveals his will through these levels. So it is not God who changes; it is our perception of God which changes.

Altogether, eleven Sefirot are named. However Keter and Da’at are unconscious and conscious dimensions of one principle; thereby conserving ten forces. The names of the Sefirot in descending order are:

- Keter – the supernal crown representing above-conscious will

- Chochmah – the highest potential of thought

- Binah – the understanding of the potential

- Da’at – the intellect of knowledge

- Chesed – sometimes referred to as Gedolah-greatness and loving-kindness

- Gevurah – sometimes referred to as Din-justice or Pachad-fear (severity/strength)

- Rachamim also known as Tiferet (mercy)

- Netzach – victory/eternity

- Hod – glory/splendor

- Yesod – foundation

- Malkuth – kingdom

9. Descending Spiritual Worlds

Medieval Kabbalists believed all things are linked to God through these emanations; thereby, making all levels in creation part of one great, gradually descending chain of being. Through these levels any lower creation reflects its particular characteristics in Supernal Divinity. Hasidic thought extends the Divine immanence of Kabbalah by believing God is the only thing that really exists – defined philosophically as monistic panentheism. Among problems considered in the Hebrew Kabbalah is the universal religious issue of the nature and origin of evil. In the views of some Kabbalists this conceives “evil” as a “quality of God,” asserting that negativity enters into the essence of the Absolute. In this view it is conceived that the Absolute needs evil to exist.

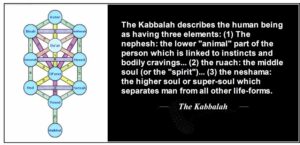

The Kabbalah describes the human being as having three elements: (1) The nephesh: the lower “animal” part of the person which is linked to instincts and bodily cravings. The nephesh is found in all humans, entering the physical body at birth. It is the source of one’s physical and psychological nature. (2) The ruach: the middle soul (or the “spirit”) which contains the moral virtues and the ability to distinguish between good and evil. (3) The neshama: the higher soul or super-soul which separates man from all other life-forms. The neshamah is related to the intellect and allows humans to enjoy and benefit from the afterlife. It allows one to have some awareness of the existence and presence of God. The (2) ruach and (3) the neshama are not implanted at birth, but can be developed over time. Their development depends on the actions and beliefs of the individual and are said to only fully exist in people awakened spiritually. The Zohar also describes fourth and fifth parts of the human soul – the chayyah and the yehidah. The chayyah is the part of the soul which allows one to have an awareness of the divine life force. The yehidah is the highest plane of the soul where one can achieve the fullest union with God as is possible. The chayyah and the yehidah do not enter into the body like the other three which is why they receive less attention than in other sections of the Zohar.

The Kabbalistic concept of reincarnation is called gilgul – a Hebrew word meaning “cycle.” Souls are seen to “cycle” through “lives” or “incarnations” becoming attached to different human bodies over time. Which body they associate with depends on their particular task in the physical world, spiritual levels of the bodies of predecessors and so on. Gilgul relates to a broader historical process in Kabbalah involving Cosmic Tikkun (Messianic rectification) and the historical dynamic of ascending Lights and descending Vessels from generation to generation. The esoteric explanations of gilgul were articulated in Jewish mysticism by Rabbi Isaac Luria in the 16th century, as part of the metaphysical purpose of Creation.

10. The History of Reincarnation in Judaism

The notion of reincarnation, while held as a mystical belief by some, is not an essential tenet of traditional Judaism. The books of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism both teach gilgul – a universal tenet in Hasidic Judaism which regards the Kabbalah as sacred and authoritative. Rabbis who believed in reincarnation include: (1) the mystical leaders Nahmanides (the Ramban) and Rabbenu Bahya ben Asher; (2) Levi ibn Habib (the Ralbah) from the 16th-century, and from the mystical school of Safed Shelomoh Alkabez, (3) Isaac Luria (the Ari) and his exponent (4) Hayyim Vital; and (5) the founder of Hasidism Yisrael Baal Shem Tov of the 18th-century, later (6) Hasidic Masters, and (7) the Lithuanian Jewish Orthodox leader and Kabbalist the Vilna Gaon. Rabbbi Isaac Luria taught new explanations of the process of gilgul and identified the reincarnations of historic Jewish figures. The idea of gilgul became popular in Jewish folklore and is found in much Yiddish literature among Ashkenazi Jews.

The main Kabbalistic text dealing with gilgul is called Shaar HaGilgulim or “The Gate of Reincarnations” which is based on the work of Rabbi Isaac Luria. It describes the deep, complex laws of reincarnation which includes the concept of gilgul being paralleled physically through pregnancy. The Kabbalistic view of gilgul is similar to the Eastern view of reincarnation in that they are an expression of divine compassion. Gilgul differs from Eastern views in that gilgul is not automatic and is neither a punishment of sin nor a reward of virtue. Gilgul is concerned with the process of the soul’s individual Tikkun (rectification). Each Jewish soul is reincarnated enough times only in order to fulfill each of the 613 Mitzvot. The souls of righteous non-Jews may be assisted through gilgulim by fulfilling the Seven Laws of Noah. Gilgul is a divine agreement for the individual soul to reincarnate to perform good works toward the goal of becoming perfected. Gilgul is also tied to the Kabbalah’s doctrine of creation where a cosmic catastrophe occurred called the “shattering of the vessels” of the Sephirot in the “world of Tohu (chaos)”. The vessels of the Sephirot broke and fell down through the spiritual Worlds until they were embeded in our physical realm as “sparks of holiness” (Nitzotzot). All Mitzvot involve performing good works because they elevate each particular Spark of holiness associated with its related commandment. Once all the Sparks are redeemed to their spiritual source, the Messianic Era begins. This theology gives cosmic significance to every human being as each person has particular tasks which only they can fulfill. Each soul is assisted through gilgul toward the Cosmic plan of bringing about Utopia on Earth – a lower World where the purpose of creation is fulfilled.

11. Important Kabbalah Links

— Kabbalah on Wikipedia – (wikipedia.org)

— Category:Kabbalah on Wikipedia – (wikipedia.org)

— List of Jewish Kabbalists – (wikipedia.org)

— Primary Texts of the Kabbalah – (wikipedia.org)

— Practical Kabbalah – (wikipedia.org)

— Christian Kabbalah – (wikipedia.org)

— Hermetic Qabalah – (wikipedia.org)

— Cabala article at Jewish Encyclopedia – (jewishencyclopedia.com)

— The Official Site of the Kabbalah Centre – (kabbalah.com)

— The Official Site of Bnei Baruch – (kabbalah.info)