This site uses affiliate links to Amazon.com Books for which IANDS can earn an affiliate commission if you click on those links and make purchases through them.

1. Introduction to Reincarnation in Christian History

Many Christians have the misconception that the concept of reincarnation means that, at the time of death, people reincarnate immediately and do not have any experiences in the spirit realms in between Earth lives. Near-death experiences prove this misconception to be untrue. Because time does not exist in the spirit world, a person can spend “eons of time” in the spirit realms, if they wish to do so, and have the freedom to decide if they want to reincarnate or not. The ultimate goal of reincarnation is to learn enough lessons from Earth lives that reincarnation is no longer necessary.

But does it make any difference whether or not one believes in reincarnation? The doctrine of reincarnation, like any dogmatic tenet, is not very important when it comes to living a spiritual life. Debating about whether reincarnation exists or not is the equivalent of debating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. There is probably no special spiritual advantage for a person to believe or not believe in reincarnation. However, reincarnation does provide a reasonable theory to account for the apparent absurdities in the dispensation of divine justice.

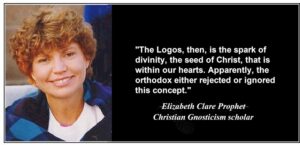

This article on reincarnation is authored by Elizabeth Clare Prophet (1939-2009) who was a minister with The Summit Lighthouse and author of several books dealing with early Christianity and many related metaphysical books, such as: Reincarnation: The Missing Link in Christianity (1997), Fallen Angels and the Origins of Evil (2000), Karma and Reincarnation (1999), The Lost Teachings of Jesus (1986), Quietly Comes the Buddha (1998), The Path to the Universal Christ (2003), Kabbalah: Key to Your Inner Power (1997), Keys to the Kingdom (2003), The Astrology of the Four Horsemen (1990), and Walking with the Master (2002).

Elizabeth Clare Prophet’s meticulous and impressive research into the history of reincarnation in the early Christian movement provides the seeker of truth a valid reason to believe that the early Church officials decided to halt the long history of reincarnation in the early Christian sects in order to further their own political purposes. The following information comes from my favorite book by Ms. Prophet, Reincarnation: The Missing Link in Christianity.

2. The Mystery of God in Humanity

Early in the fourth century, while Bishop Alexander of Alexandria was expounding on the Trinity to his flock, a theological tsunami was born.

A Libyan priest named Arius stood up and posed the following simple question:

“If the Father begat the Son, he that was begotten had a beginning of existence.”

In other words, if the Father is the parent of the Son, then didn’t the Son have a beginning?

Apparently, no one had put it this way before. For many bishops, Arius spoke heresy when he said that the Son had a beginning. A debate erupted, led by Arius on the one side and by Alexander and his deacon Athanasius on the other. Athanasius became the Church’s lead fighter in a struggle that lasted his entire life.

In 320 A.D., Alexander held a Council of Alexandria to condemn the errors of Arius. But this did not stop the controversy. The Church had nearly split over the issue when the controversy reached the ears of the Roman emperor Constantine. He decided to resolve it himself in a move that permanently changed the course of Christianity.

The orthodox accused the Arians of attempting to lower the Son by saying he had a beginning. But, in fact, the Arians gave him an exalted position, honoring him as “first among creatures.” Arius described the Son as one who became “perfect God, only begotten and unchangeable,” but also argued that he had an origin.

The Arian controversy was really about the nature of humanity and how we are saved. It involved two pictures of Jesus Christ: Either he was a God who had always been God or he was a human who became God’s Son.

If he was a human who became God’s Son, then that implied that other humans could also become Sons of God. This idea was unacceptable to the orthodox, hence their insistence that Jesus had always been God and was entirely different from all created beings. As we shall see, the Church’s theological position was, in part, dictated by its political needs. The Arian position had the potential to erode the authority of the Church since it implied that the soul did not need the Church to achieve salvation.

The outcome of the Arian controversy was crucial to the Church’s position on both reincarnation and the soul’s opportunity to become one with God. Earlier, the Church decided that the human soul is not now and never has been a part of God. Instead it belongs to the material world and is separated from God by a great chasm.

Rejecting the idea that the soul is immortal and spiritual, which was a part of Christian thought at the time of Clement of Alexandria and Origen, the Fathers developed the concept of “creatio ex nihilo“, creation out of nothing. If the soul were not a part of God, the orthodox theologians reasoned, it could not have been created out of his essence.

The doctrine persists to this day. By denying man’s divine origin and potential, the doctrine of creation out of nothing rules out both pre-existence and reincarnation. Once the Church adopted the doctrine, it was only a matter of time before it rejected both Origenism and Arianism. In fact, the Arian controversy was only one salvo in the battle to eradicate the mystical tradition Origen represented.

Origen and his predecessor, Clement of Alexandria, lived in a Platonist world. For them it was a given that there is an invisible spiritual world which is permanent and a visible material world that is changeable. The soul belongs to the spiritual world, while the body belongs to the material world.

In the Platonists’ view, the world and everything in it is not created but emanates from God, the One. Souls come from the Divine Mind, and even when they are encased in bodily form, they retain their link to the Source.

Clement tells us that humanity is “of celestial birth, being a plant of heavenly origin.” Origen taught that man, having been made after the “image and likeness of God,” has “a kind of blood-relationship with God.”

While Clement and Origen were teaching in Alexandria, another group of Fathers was developing a counter-theology. They rejected the Greek concept of the soul in favor of a new and unheard of idea: The soul is not a part of the spiritual world at all; but, like the body, it is part of the mutable material world.

They based their theology on the changeability of the soul. How could the soul be divine and immortal, they asked, if it is capable of changing, falling and sinning? Because it is capable of change, they reasoned, it cannot be like God, who is unchangeable.

Origen took up the problem of the soul’s changeability but came up with a different solution. He suggested that the soul was created immortal and that even though it fell (for which he suggests various reasons), it still has the power to restore itself to its original state.

For him the soul is poised between spirit and matter and can choose union with either:

“The will of this soul is something intermediate between the flesh and the spirit, undoubtedly serving and obeying one of the two, whichever it has chosen to obey.” If the soul chooses to join with spirit, Origen wrote, “the spirit will become one with it.”

This new theology, which linked the soul with the body, led to the ruling out of pre-existence. If the soul is material and not spiritual, then it cannot have existed before the body. As Gregory of Nyssa wrote:

“Neither does the soul exist before the body, nor the body apart from the soul, but … there is only a single origin for both of them.”

When is the soul created then? The Fathers came up with an improbable answer: at the same time as the body – at conception. “God is daily making souls,” wrote Church Father Jerome. If souls and bodies are created at the same time, both pre-existence and reincarnation are out of the question since they imply that souls exist before bodies and can be attached to different bodies in succession.

The Church still teaches the soul is created at the same time as the body and therefore the soul and the body are a unit.

This kind of thinking led straight to the Arian controversy. Now that the Church had denied that the soul pre-exists the body and that it belongs to the spiritual world, it also denied that souls, bodies and the created world emanated from God.

3. The Arian Controversy

When Arius asked whether the Son had a beginning, he was, in effect, pointing out a fundamental flaw in that doctrine. The doctrine did not clarify the nature of Christ. So he was asking: If there is an abyss between Creator and creation, where does Christ belong? Was he created out of nothing like the rest of the creatures? Or was he part of God? If so, then how and why did he take on human form?

The Church tells us that the Arian controversy was a struggle against blasphemers who said Christ was not God. But the crucial issue in the debate was: How is humanity saved – through emulating Jesus or through worshiping him?

The Arians claimed that Jesus became God’s Son and thereby demonstrated a universal principle that all created beings can follow. But the Orthodox Church said that he had always been God’s Son, was of the same essence as God (and therefore was God) and could not be imitated by mere creatures, who lack God’s essence. Salvation could come only by accessing God’s grace via the Church.

The Arians believed that human beings could also be adopted as Sons of God by imitating Christ. For the Arians, the incarnation of Christ was designed to show us that we can follow Jesus and become, as Paul said, “joint heirs with Christ.”

The Orthodox Church, by creating a gulf between Jesus and the rest of us, denied that we could become Sons in the same way he did. The reason why the Church had such a hard time seeing Jesus’ humanity was that they could not understand how anyone could be human and divine at the same time. Either Jesus was human (and therefore changeable) or he was divine (and therefore unchangeable).

The orthodox vision of Jesus as God is based in part on a misunderstanding of the Gospel of John. John tells us:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God … All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made.” Later John tells us the “the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.”

The orthodox concluded from these passages that Jesus Christ is God, the Word, made flesh.

What they didn’t understand was that when John called Jesus “the Word,” he was referring to the Greek tradition of the Logos. When John tells us that the Word created everything, he uses the Greek term for Word – “Logos.” In Greek thought, Logos describes the part of God that acts in the world. Philo called the Logos “God’s Likeness, by whom the whole cosmos was fashioned.” Origen called it the soul that holds the universe together.

Philo believed that great human beings like Moses could personify the Logos. Thus, when John writes that Jesus is the Logos, he does not mean that the man Jesus has always been God the Logos. What John is telling us is that Jesus the man became the Logos, the Christ.

Some early theologians believed that everyone has that opportunity. Clement tells us that each human has the “image of the Word (Logos)” within him and that it is for this reason that Genesis says that humanity is made “in the image and likeness of God.”

The Logos, then, is the spark of divinity, the seed of Christ, that is within our hearts. Apparently the orthodox either rejected or ignored this concept.

We should understand that Jesus became the Logos just as he became the Christ. But that didn’t mean he was the only one who could ever do it. Jesus explained this mystery when he broke the bread at the Last Supper. He took a single loaf, symbolizing the one Logos, the one Christ, and broke it and said, “This is my body, which is broken for you.”

He was teaching the disciples that there is one absolute God and one Universal Christ, or Logos, but that the body of that Universal Christ can be broken and each piece will still retain all the qualities of the whole. He was telling them that the seed of Christ was within them, that he had come to quicken it and that the Christ was not diminished no matter how many times his body was broken. The smallest fragment of God, Logos, or Christ, contains the entire nature of Christ’s divinity – which, to this day, he would make our own.

The orthodox misunderstood Jesus’ teaching because they were unable to accept the reality that each human being has both a human and a divine nature and the potential to become wholly divine. They didn’t understand the human and the divine in Jesus and therefore they could not understand the human and the divine within themselves. Having seen the weakness of human nature, they thought they had to deny the divine nature that occasionally flashes forth even in the lowliest of human beings.

The Church did not understand (or could not admit) that Jesus came to demonstrate the process by which the human nature is transformed into the divine. But Origen had found it easy to explain:

He believed that the human and divine natures can be woven together day by day. He tells us that in Jesus “the divine and human nature began to interpenetrate in such a way that the human nature, by its communion with the divine, would itself become divine.” Origen tells us that the option for the transformation of humanity into divinity is available not just for Jesus but for “all who take up in faith the life which Jesus taught.”

Origen did not hesitate to describe the relationship of human beings to the Son. He believed that we contain the same essence as the Father and the Son:

“We, therefore, having been made according to the image, have the Son, the original, as the truth of the noble qualities that are within us. And what we are to the Son, such is the Son to the Father, who is the truth.”

Since we have the noble qualities of the Son within us, we can undergo the process of divinization (at-onement with God).

To the Arians, the divinization process was essential to salvation; to the orthodox, it was heresy. In 324 A.D., the Roman emperor Constantine, who had embraced Christianity twelve years earlier, entered the Arian controversy. He wrote a letter to Arius and Bishop Alexander urging them to reconcile their differences, and he sent Bishop Hosius of Corduba to Alexandria to deliver it. But his letter could not calm the storm that raged over the nature of God – and man. Constantine realized that he would have to do more if he wanted to resolve the impasse.

4. The Council of Nicea

In June, 325 A.D., the Council of Nicea opened and continued for two months, with Constantine attending. The bishops modified an existing creed to fit their purposes. The creed, with some changes made at a later fourth century council, is still given today in many churches. The Nicene Creed, as it came to be called, takes elaborate care by repeating several redundancies to identify the Son with the Father rather than with the creation:

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible; and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of his Father, of the substance of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father. By whom all things were made … Who … was incarnate and was made human …”

Only two bishops, along with Arius, refused to sign the creed. Constantine banished them from the empire, while the other bishops went on to celebrate their unity in a great feast at the imperial palace.

The creed is much more than an affirmation of Jesus’ divinity. It is also an affirmation of our separation from God and Christ. It takes great pains to describe Jesus as God in order to deny that he is part of God’s creation. He is “begotten, not made,” therefore totally separate from us, the created beings. As scholar George Leonard Prestige writes, the Nicene Creed’s description of Jesus tells us “that the Son of God bears no resemblance to the … creatures.”

The description of Jesus as the only Son of God is carried forward in the Apostles’ Creed, which is used in many Protestant churches today. It reads: “I believe in God, the Father Almighty … I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord.” But even that language – calling Jesus God’s only Son – denies that we can ever attain the sonship that Jesus did.

Christians may be interested to know that many scholars analyzing the Bible now believe that Jesus never claimed to be the only Son of God. This was a later development based on a misinterpretation of the Gospel of John.

There is further evidence to suggest that Jesus believed all people could achieve the goal of becoming Sons of God. But the churches, by retaining these creeds, remain in bondage to Constantine and his three hundred bishops.

Some of the bishops who attended the council were uncomfortable with the council’s definition of the Son and thought they might have gone too far. But the emperor, in a letter sent to the bishops who were not in attendance at Nicea, required that they accept “this truly divine injunction.”

Constantine said that since the council’s decision had been “determined in the holy assemblies of the bishops,” the Church officials must regard it as “indicative of the divine will.”

The Roman god Constantine had spoken. Clearly, he had concluded that the orthodox position was more conducive to a strong and unified Church than the Arian position and that it therefore must be upheld.

Constantine also took the opportunity to inaugurate the first systematic government persecution of dissident Christians. He issued an edict against “heretics,” calling them “haters and enemies of truth and life, in league with destruction.”

Even though he had begun his reign with an edict of religious toleration, he now forbade the heretics (mostly Arians) to assemble in any public or private place, including private homes, and ordered that they be deprived of “every gathering point for [their] superstitious meetings,” including “all the houses of prayer.” These were to be given to the orthodox Church.

The heretical teachers were forced to flee, and many of their students were coerced back into the orthodox fold. The emperor also ordered a search for their books, which were to be confiscated and destroyed. Hiding the works of Arius carried a severe penalty – the death sentence.

Nicea, nevertheless, marked the beginning of the end of the concepts of both pre-existence, reincarnation, and salvation through union with God in Christian doctrine. It took another two hundred years for the ideas to be expunged.

But Constantine had given the Church the tools with which to do it when he molded Christianity in his own image and made Jesus the only Son of God. From now on, the Church would become representative of a capricious and autocratic God – a God who was not unlike Constantine and other Roman emperors.

Tertullian, a stanch anti-Origenian and a father of the Church, had this to say about those who believed in reincarnation and not the resurrection of the dead:

“What a panorama of spectacle on that day [the Resurrection]! What sight should I turn to first to laugh and applaud? … Wise philosophers, blushing before their students as they burn together, the followers to whom they taught that the world is no concern of God’s, whom they assured that either they had no souls at all or that what souls they had would never return to their former bodies? These are things of greater delight, I believe, than a circus, both kinds of theater, and any stadium.”

Tertullian was a great influence in having so-called “heretics” put to death.

5. The Fifth General Council

After Constantine and Nicea, Origen’s writings had continued to be popular among those seeking clarification about the nature of Christ, the destiny of the soul and the manner of the resurrection. Some of the more educated monks had taken Origen’s ideas and were using them in mystical practices with the aim of becoming one with God.

Toward the end of the fourth century, orthodox theologians again began to attack Origen. Their chief areas of difficulty with Origen’s thought were his teachings on the nature of God and Christ, the resurrection and the pre-existence of the soul.

Their criticisms, which were often based on ignorance and an inadequate understanding, found an audience in high places and led to the Church’s rejection of Origenism and reincarnation. The Church’s need to appeal to the uneducated masses prevailed over Origen’s coolheaded logic.

The bishop of Cyprus, Epiphanius, claimed that Origen denied the resurrection of the flesh. However, as scholar Jon Dechow has demonstrated, Epiphanius neither understood nor dealt with Origen’s ideas. Nevertheless, he was able to convince the Church that Origen’s ideas were incompatible with the merging literalist theology. On the basis of Ephiphanius’ writings, Origenism would be finally condemned a century and a half later.

Jerome believed that resurrection bodies would be flesh and blood, complete with genitals – which, however, would not be used in the hereafter. But Origenists believed the resurrection bodies would be spiritual.

The Origenist controversy spread to monasteries in the Egyptian desert, especially at Nitria, home to about five thousand monks. There were two kinds of monks in Egypt – the simple and uneducated, who composed the majority, and the Origenists, an educated minority.

The controversy solidified around the question of whether God had a body that could be seen and touched. The simple monks believed that he did. But the Origenists thought that God was invisible and transcendent. The simple monks could not fathom Origen’s mystical speculations on the nature of God.

In 399 A.D., Bishop Theophilus wrote a letter defending the Origenist position. At this, the simple monks flocked to Alexandria, rioting in the streets and even threatening to kill Theophilus.

The bishop quickly reversed himself, telling the monks that he could now see that God did indeed have a body: “In seeing you, I behold the face of God.” Theophilus’ sudden switch was the catalyst for a series of events that led to the condemnation of Origen and the burning of the Nitrian monastery.

Under Theodosius, Christians, who had been persecuted for so many years, now became the persecutors. God made in man’s image proved to be an intolerant one. The orthodox Christians practiced sanctions and violence against all heretics (including Gnostics and Origenists), pagans and Jews. In this climate, it became dangerous to profess the ideas of innate divinity and the pursuit of union with God.

It may have been during the reign of Theodosius that the Gnostic Nag Hammadi manuscripts were buried – perhaps by Origenist monks. For while the Origenist monks were not openly Gnostic, they would have been sympathetic to the Gnostic viewpoint and may have hidden the books after they became too hot to handle.

The Origenist monks of the desert did not accept Bishop Theophilus’ condemnations. They continued to practice their beliefs in Palestine into the sixth century until a series of events drove Origenism underground for good.

Justinian (ruled 527-565 A.D.) was the most able emperor since Constantine – and the most active in meddling with Christian theology. Justinian issued edicts that he expected the Church to rubber-stamp, appointed bishops and even imprisoned the pope.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire at the end of the fifth century, Constantinople remained the capital of the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire. The story of how Origenism ultimately came to be rejected involves the kind of labyrinthine power plays that the imperial court became famous for.

Around 543 A.D., Justinian seems to have taken the side of the anti-Origenists since he issued an edict condemning ten principles of Origenism, including pre-existence. It declared “anathema to Origen … and to whomsoever there is who thinks thus.” In other words, Origen and anyone who believes in these propositions would be eternally damned. A local council at Constantinople ratified the edict, which all bishops were required to sign.

In 553 A.D., Justinian convoked the Fifth General Council of the Church to discuss the controversy over the so-called “Three Chapters.” These were writings of three Originist theologians whose views bordered on the heretical. Justinian wanted the writings to be condemned and he expected the council to oblige him.

He had been trying to coerce the pope into agreeing with him since 545 A.D. He had essentially arrested the pope in Rome and brought him to Constantinople, where he held him for four years. When the pope escaped and later refused to attend the council, Justinian went ahead and convened it without him.

This council produced fourteen new anathemas against the authors of the Three Chapters and other Christian theologians. The eleventh anathema included Origen’s name in a list of heretics.

The first anathema reads:

“If anyone asserts the fabulous pre-existence of souls, and shall assert the monstrous restoration which follows from it: let him be anathema.” (“Restoration” means the return of the soul to union with God. Origenists believed that this took place through a path of reincarnation.)

It would seem that the death blow had been struck against Origenism and reincarnation in Christianity.

After the council, the Origenist monks were expelled from their Palestinian monastery, some bishops were deposed and once again Origen’s writings were destroyed. The anti-Origenist monks had won. The emperor had come down firmly on their side.

In theory, it would seem that the missing papal approval of the anathemas leaves a doctrinal loophole for the belief in reincarnation among all Christians today. But since the Church accepted the anathemas in practice, the result of the council was to end belief in reincarnation in orthodox Christianity.

In any case, the argument is moot. Sooner or later the Church probably would have forbade the beliefs. When the Church codified its denial of the divine origin of the soul (at Nicea in 325 A.D.), it started a chain reaction that led directly to the curse on Origen.

Church councils notwithstanding, mystics in the Church continued to practice divinization. They followed Origen’s ideas, still seeking union with God.

But the Christian mystics were continually dogged by charges of heresy. At the same time as the Church was rejecting reincarnation, it was accepting original sin, a doctrine that made it even more difficult for mystics to practice.

6. Conclusion

With the condemnation of Origen, so much that is implied in reincarnation was officially stigmatized as heresy that the possibility of a direct confrontation with this belief was effectively removed from the church. In dismissing Origen from its midst, the church only indirectly addressed itself to the issue of reincarnation. The encounter with Origenism did, however, draw decisive lines in the matter of pre-existence, the resurrection of the dead, and the relationship between body and soul. What an examination of Origen and the church does achieve, however, is to show where the reincarnationist will come into collision with the posture of orthodoxy. The extent to which he may wish to retreat from such a collision is of course a matter of personal conscience.

With the Council of 553 A.D. one can just about close the book on this entire controversy within the church. There are merely two footnotes to be added to the story, emerging from church councils in 1274 and 1439 A.D. In the Council of Lyons, in 1274 A.D., it was stated that after death the soul goes promptly either to heaven or to hell. On the Day of Judgment, all will stand before the tribunal of Christ with their bodies to render account of what they have done. The Council of Florence of 1439 A.D. uses almost the same wording to describe the swift passage of the soul either to heaven or to hell. Implicit in both of these councils is the assumption that the soul does not again venture into physical bodies.