This site uses affiliate links to Amazon.com Books for which IANDS can earn an affiliate commission if you click on those links and make purchases through them.

1. Introduction to Frightening NDEs

While many near-death experiences (NDEs) are described as peaceful or even blissful, a significant number of people report encounters that are distressing, frightening, or deeply unsettling. These experiences, often termed “frightening NDEs,” can involve intense feelings of fear, isolation, or darkness, and can even include vivid perceptions of hostile or threatening environments. Unlike typical NDEs, which can provide comfort and new insight, frightening NDEs can leave experiencers grappling with anxiety, confusion, and a fear of death rather than reassurance. The emotional and psychological toll of such experiences can be profound, creating lasting challenges as individuals work to process and integrate these encounters. As they search for meaning and understanding, those who endure frightening NDEs may face an especially difficult journey toward healing and acceptance, often seeking support from others who can empathize with their uniquely intense experience.

2. About This Article

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Kenneth Ring, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of Connecticut. His official website is www.kenring.org. His official blog is www.kenringblog.com. His NDE books can be purchased here – www.kenring.org/books.html. Reprint requests should be addressed to Dr. Ring.

ABOUT THE JOURNAL: The Journal of Near-Death Studies from the International Association for Near-Death Studies (IANDS.org) is the only peer-reviewed scholarly journal devoted exclusively to the field of the study of near-death experiences (NDEs). To access the latest issues from the previous three years and receive new issues of the quarterly journal, you must subscribe to the journal simply by joining and becoming a member of IANDS. The Journal of Near-Death Studies also encourages submission of articles. Basic information about the journal is available.

ABOUT IANDS: Your IANDS membership helps provide the financial support for IANDS to pursue their mission of encouraging independent research into NDEs and educating the world about near-death and similar experiences — and their effects and implications. In return, IANDS will give you special access to members-only sections of their website including the Index to the Periodical NDE Literature from 1877 through 2011, their Vital Signs newsletter, annual IANDS conference and educational offerings. Other important links to IANDS include: NDE Accounts – NDE Archives – Store – Support – Publications – Brochures – Facebook – Twitter – YouTube.

The following is a reprint by permission of the article “Solving the Riddle of Frightening Near-Death Experiences: Some Testable Hypotheses and a Perspective Based on A Course in Miracles” by Kenneth Ring, Ph.D. published in the Journal of Near-Death Studies, 13(1) Fall 1994, Human Sciences Press, Inc.

3. Solving the Riddle of Frightening Near-Death Experiences: Some Testable Hypotheses and a Perspective Based on A Course in Miracles

ABSTRACT: This article discusses three varieties of frightening near-death experiences (NDEs), as distinguished in the typology of Bruce Greyson and Nancy Evans Bush (1992). “Inverted” and hellish NDEs are analyzed in terms of the terror of ego-death that results in resistance to the experience and inability to surrender to it. The third kind, experiences of a “meaningless void,” may reflect an “emergence reaction” to inadequate anesthesia. Testable hypotheses stemming from this analysis are presented, and the relevance of the conception of reality based on teaching found in A Course in Miracles for understanding NDEs is indicated. Finally, the ontological status of both transcendent and frightening NDEs is briefly considered.

In 1978, a dark cloud of chilling testimony began to penetrate into the previously luminous sky of reports of near-death experiences (NDEs). Maurice Rawlings, a cardiologist, in his book Beyond Death’s Door (1978), claimed to have found many cases of persons who described frightening or even hellish encounters in their near-death episodes and suggested that their hitherto unnoticed existence was largely attributable to the fact that most near-death researchers had interviewed their respondents too long after the actual near-death crisis to detect these unsettling features. By then, Rawlings asserted, the mechanisms of repression and selective forgetting would already have obliterated all traces of such deeply traumatic visions.

Although questions were immediately raised about the validity of Rawlings’ conclusions, because of his flawed methodology and concerns about his tendentiousness owing to his strongly held fundamentalist religious views (Sabom, 1979, Ring, 1980), there now seems to belittle doubt that Rawlings was right about one thing: in the words of Margot Grey, “negative encounters, while infrequent, do however definitely exist” (1985, p. 56). Indeed, in addition to Grey’s findings and an early survey of such cases by George Gallup (Gallup and Proctor, 1982), there has recently been a spate of articles (Atwater, 1992; Greyson and Bush, 1992; Rogo, 1989) that have called our attention to the indisputable occurrence of frightening NDEs and have urged that further research be devoted to exploring the factors that cause these strikingly different deviations from the classic form of the radiant NDE.

The only one of these papers actually to present new findings on these experiences for us to ponder, however, was the one by Bruce Greyson and Nancy Evans Bush (1992) that summarized the results of an informal collection of 50 cases of frightening NDEs culled from the authors’ files of letters and from responses to a request for such experiences that they had placed in an NDE newsletter. The findings from their survey allowed Greyson and Bush to propose a tentative typology of frightening NDEs, but, as they admitted, most of the obvious questions about these experiences remain unanswered. Are certain persons especially likely to have frightening NDEs, for example, and if so, what are their defining characteristics? Or, on the other hand, are there certain conditions associated with the near-death event itself that conduce to these episodes? And, regardless of the factors that prompt frightening NDEs, do the aftereffects of these experiences, as Greyson and Bush hinted, differ significantly from those of the usual ecstatic NDE, and if so, precisely how? All these questions, which should clearly be at the heart of any systematic inquiry into these disturbing experiences, have yet to be explored in any careful way.

As a prelude to such research, this paper offers some testable hypotheses pertaining to these fundamental issues. In my discussion of these hypotheses and their rationale, I will make use of the tripartite typology of frightening NDEs suggested by Greyson and Bush (1992). They distinguish three principal varieties of such experiences, which I will call “inverted” NDEs, hellish NDEs, and experiences of a “meaningless void.”

4. “Inverted” NDEs

What I am calling an “inverted” NDE is merely an experience that has exactly the same form as the classic NDE, but is perceived in terms of a negatively-toned affective filter. That is, the person reports all the usual events – having an out-of-body experience, going through a tunnel, encountering a light, and so on – but responds to these features from a standpoint of fear rather than peaceful acceptance. Greyson and Bush gave a number of examples of this kind in their paper, as did Grey (1985) in her chapter on the subject where she also, by the way, classified frightening NDEs in a fashion similar to that of Greyson and Bush.

Why should some persons experience these common features of NDEs as frightening? Although not many cases of “inverted” NDEs have been described in the literature, nevertheless the answer already seems clear, and Greyson and Bush themselves have put their finger on it (p. 99): The person who responds this way is likely to be terrified by the prospect of losing one’s ego in the process. As a result, the experience of dying is resisted strenuously rather than being surrendered to. It is this very resistance that creates the filter of increasing fear that comes to pervade the entire experience.

The cases Greyson and Bush provided to illustrate “inverted” NDEs offer abundant testimony for this kind of reaction among their respondents. Indeed, the sense of wanting to remain in control and consequently of reluctance to give oneself over to the experience of dying are among the defining features of these accounts, as I read them. One of the women they quoted, for example, said that during her OBE, “I became frightened and I remember strongly the feeling I didn’t like what I saw and what was happening. I shouted [within herself], I don’t like this!'” (p. 99). Another woman, describing a childhood NDE, averred, “That night I was picked up, unwillingly, by a lady… She carried me in her arms … swiftly taking me somewhere I did not want to go … and kept trying to explain that I had to go, and nothing could prevent it, no matter how much I didn’t want to leave” (p. 99). A third instance of this same unwillingness to surrender came from the account of a 64 year-old man who related that as he felt himself flying through a funnel and nearing its end, “I felt that I did not want to go on … I vividly remember screaming, ‘God, I’m not ready; please help me’ ” (p. 100).

In my own research I have also encountered a few cases of this kind. One, where the terror of ego-death became self-evident to the respondent herself, involved a woman I’ll call J.T. J.T. had been living in Central America in 1979 when she became ill and had her NDE. She was being driven to a local first-aid station but before she arrived, she had already begun to feel herself close to death. As she described her experience to me, she said that at the beginning…

“A snowballing effect occurred. As all of my energy started rolling inward, I was frantic. It was living hell and I never experienced such terror in my life. It was the death of my ego. It was accompanied by an incredible and totally consuming terror. Also, great struggle and upheavals were involved in the passing away of my ego … Most of my memories of this juncture are taken up with my struggle and terror. The image I retain is the simile of a small child being dragged somewhere against his will and kicking and screaming the whole way.” (Ring, 1984, p. 9)

What makes this case particularly instructive, however, is that J.T. also became simultaneously aware of a detached “witness consciousness” within herself, which was simply noting this struggle dispassionately, and as she experienced the crossing over into death itself, she said:

“Someone was watching all this and that someone was still me, and yet the me, as I was accustomed to think of me, was dead. The me (SELF) was watching it all and had witnessed the death of me (ego). It was all very confusing and yet very clear at the same time.” (Ring, 1984, p. 9)

It’s just here that we find a new element entering into these “inverted” NDEs, but one that is certainly implied by our hypothesis. Look at what happens next, when J.T. surrenders:

“Concurrent with this realization, I surrendered to the force and powers that be, I gave up and “said” in effect, “OK, I give up, I’ll go quietly and peacefully…” I felt a loving presence surrounding me and in me. The space was composed of that presence of love and peace … It was a lovely place to be; very peaceful, total harmony, everything was there…” (Ring, p. 9)

In short, at this point, the “inversion” rights itself, and the experience then reverts to the classic form of the NDE which, indeed, J.T. went on to have, including a very powerful life review.

Letting go, releasing oneself completely to the numinous power of the NDE, appears therefore to be the key to the prison door of fear that dominates these experiences and thus the means of escaping what now appears to be only the initial dread of an “inverted” NDE. This implies, of course, that experiences of this type can be expected to convert themselves into the familiar classic form of the NDE if they persist long enough to allow the process of surrender to begin, or if the individual is simply overwhelmed by the intrinsic power of the NDE itself.

Other researchers concerned with frightening NDEs have in fact already noted exactly this sequence of negative-to-positive in some of their cases of this kind. For example, in an early survey of NDEs in the American Northwest, James Lindley, Sethyn Bryan and Bob Conley (1981) noted, “Most negative experiences begin with a rush of fear or panic or with a vision of wrathful or fearful creatures. These are usually transformed, at some point, into a positive experience in which all negativity vanishes and the first stage of death (peacefulness) is achieved” (p. 113). Greyson and Bush also provided two vivid examples of this sort in their paper where their introductory remarks clearly show that their interpretation of these cases is virtually identical to the one advanced here: “Since this type of distressing experience shares many descriptive features of the peaceful type, it is reasonable to regard it as a variant of the prototypical near-death experience. Supporting that view are the following examples of phenomenologically prototypical but distressing experiences that convert to peaceful ones once the individual stops fighting the experience and accepts it” (p. 100).

NDE researchers are by no means alone in positing a direct connection between the initial response – resistance versus acceptance – of the individual and the way in which a transcendental experience is processed. Explorers of the world of psychedelic voyages have also found the same relationship as that discussed here in connection with “inverted” NDEs. Since it is well known (Grof and Halifax, 1977; Ring, 1988; Rogo, 1984, 1989; Siegel and Hirschman, 1984) that psychedelic experiences can sometimes afford experiences that are virtually indistinguishable from NDEs, these observations are most pertinent to and provide an additional source of support for my hypothesis.

One of the earliest investigators to speak to this point was the man whom many regard as having helped to launch the modern psychedelic movement through his writings about his own experiences, Aldous Huxley. In one of his first books on the subject, Heaven and Hell (Huxley, 1963), Huxley, in addressing mescaline experiences, presciently remarked,

“… (N)egative experiences may be induced by purely psychological means. Fear and anger bar the way to the heavenly Other World and plunge the mescaline taker into hell … Negative emotions – the fear which is the absence of confidence, the hatred, anger or malice which exclude love – are the guarantee that visionary experience, if and when it comes, shall be appalling.” (p. 137-138)

Recently, there has been additional evidence from psychedelic research that bears out Huxley’s claim and its implied counter-instance. Igor Kungurtsev is a Russian psychiatrist, now living in the United States, who has done important research on alcoholism using the dissociative anesthetic, ketamine. Using it in an alcoholism treatment facility in Russia in doses ranging from one-tenth to one-sixth of the amounts standard in surgery, Kungurtsev (1991) found that many of his patients reported experiences with many features of classic NDEs. According to him:

“At the beginning of ketamine sessions, people often experience the separation of consciousness from the body and the dissolving of the body ego. For many patients, it is a profound insight that they can exist without their bodies as pure consciousness or pure spirit … They describe an ocean of brilliant white light, sometimes a golden white light, which is filled with love, bliss and energy. After coming back to ordinary consciousness, they feel sure that they have had contact with a higher power … and now believe that some part of them will continue to exist after death. (Kungurtsev, 1991, p. 4)

What is particularly relevant to us here, however, is Kungurtsev’s further observation that in these ketamine induced NDE-type episodes, there was a…

“correlation between the type of personality and the type of experience under the influence of ketamine. People who are very controlled and have difficulties letting go … often have negative experiences with ketamine. For them, the dissolving of the individual sense of self is horrible. For other patients who are more relaxed and are able to surrender … the experience is usually blissful, even ecstatic.” (1991, p. 4)

To sum up these remarks about “inverted” NDEs, then, the hypothesis offered here, supported by the data I’ve cited, suggests that the primary reason for the occurrence of these experiences is the fear unto terror associated with the prospect of imminent ego-death. Thus, those individuals who are unable to let go, or who enter the experience with undue apprehension for whatever reason (great situational fear, personal rigidity, massive religious indoctrination concerning the existence of a literal hell, etc.) would be expected to undergo “inverted” NDEs, at least to begin with. A further implication of this hypothesis, as we have seen, is that such experiences may, in time, lose their horrific grip and convert themselves into the more common beatific NDE. A detailed study of a further collection of such cases, then, should show this negative-to-positive sequence in many instances of extended NDEs.

5. Hellish NDEs

Episodes of so-called hellish NDEs are in my opinion, and Grey’s (1985) as well, merely more intense versions of “inverted” NDEs in which there is also a predominance of imagery suggestive of an archetypal hell and associated demonic entities. Psychodynamically, the underlying factors prompting these experiences should be quite similar to those of “inverted” NDEs since the former would seem to be largely culturally-derived elaborations of the latter.

One difficulty with this argument, however, is that it fails to square with one of the observations made by Greyson and Bush about this type of frightening NDE. My position implies that like “inverted” NDEs, hellish instances also ought to convert into the positive variety with time. Nevertheless, Greyson and Bush contradicted this assumption in saying that the typical hellish NDE “appears not to convert to a peaceful one with time” (p. 105). Still, as they also concede, their sample of cases here is the smallest of any of their three categories (they do not say exactly how many they have), and perhaps there are exceptions to their tentative generalization.

Indeed, as I will show, there do in fact seem to be such cases. Not only does Grey (1985, pp. 65-66) appear to provide an instance of this kind, but one of the most dramatically gripping NDE cases that I have yet encountered is a clear-cut example of one (Corneille, 1989). On June 1, 1985, Howard Storm, an art professor, found himself in Paris on the last day of a European tour he had been conducting for students. Suddenly, he screamed in pain and collapsed, the victim of a perforated intestine, which is often fatal. He was rushed to a hospital, but the necessary operation was delayed for many hours and Storm experienced pain so unendurable that, he said, had he had the means to kill himself, he would have. At one point in his ordeal, he found himself standing next to his physical body and, because he was an atheist and expected that death would be followed by the extinction of his consciousness, he was extremely baffled and disconcerted by this perception of undeniable reality. His wife and hospital roommate proving unresponsive to his pleas, Storm then found himself travelling through a dark region with a group of beings who had appeared benign at first, but who soon proved unrelentingly hostile. Eventually, they taunted Storm and then began beating and kicking him to the point where Storm felt physically annihilated, parts of his body having been severed. At this moment of complete despair and exhaustion, Storm heard a voice within him urging him to pray, but because of his life-long atheism, he rejected this action as completely unacceptable and contemptibly hypocritical. The voice continued to insist, however, and Storm ultimately yielded. His prayer, “Jesus, save me!,” caused the hostile beings to disperse, but Storm still found himself utterly alone and now apparently abandoned by all. Not for long, however: a speck of light that soon grew into an enormous brilliant glow began hurtling toward Storm, engulfed him, and swept him up into what can only be described as a “heavenly journey” that Storm represented as a dazzling encounter with a divine power, in which he was flooded with intense, overwhelming love and cosmic knowledge. The experience had such a profound impact on Storm that he eventually left his position as an art professor and is now a minister in Ohio (H. Storm, personal communication, December 15, 1992).

I will examine some further aspects of Storm’s case in a moment in order to show how it exemplifies my thesis about the effects of resistance to transcendental experience, but before doing so I want to draw on another case of an NDE to illustrate the nature of this conversion from hell to heaven. In this instance, however, it is a fictional NDE.

Jacob Singer is the protagonist of a film written by Bruce Joel Rubin – who also wrote the script for the popular film, Ghost (Rubin, Zucker, and Weinstein, 1990), which charts a comedic NDE course called Jacob’s Ladder (Rubin, Lyne, and Marshall, 1991). The film tells the story of a Vietnam veteran who is apparently the victim of post traumatic stress disorder and who experiences a series of extremely frightening flashbacks, as well as highly disturbing and mentally destabilizing events in his personal life after the war, when he is again living in New York (Rubin’s visual metaphor for hell). Ultimately, however, these terrifying visions and experiences culminate in an epiphany of light in which Singer is reunited with a son of his who had previously died. It is not until the end of the film that the viewer realizes with astonishment that the entire film has been told from the standpoint of Singer’s NDE (he has actually died on a military operating table in Vietnam), and that what one has witnessed has been solely the internal struggle of a man to become free of his own egoic attachments and fears. Rubin, who spent two years living in the Orient, including three months at a Tibetan monastery, and who is very conversant with Eastern spiritual traditions, has furnished an extremely illuminating commentary about the main themes of his film (Rubin, 1990) that also lucidly sums up the argument I am making here. The following excerpt, then, will serve to encapsulate the general thesis I am advancing for both “inverted” and hellish NDEs:

“To me, Jacob’s Ladder was not simply about one man’s struggle, but everyman’s struggle. Learning to let go of life is, in biblical terms, the key to infinite life. I wanted to dramatize what Louis [the “angelic” chiropractor in the film, Jacob’s “spiritual guide,” as it were] tells Jacob when discussing the teachings of Meister Eckhart, the German mystic and theologian. Heaven and hell are the same place. If you are afraid of dying, you experience demons tearing your flesh away. If you embrace it, you will see angels freeing you from your flesh.

“In Eastern religions, it is not the body that dies, but the illusion of the body. Death is an experience of ego loss. One loses the sense of separation between one’s finite self and the larger universe. In Eastern terms, this separation is illusory and death is a disillusioning experience. It is a moment of truth. You become aware of your oneness with all existence, a oneness that has always been there.

“If you are not prepared to be stripped of your illusions, death will be a painful process. If you have spent a lifetime angrily fighting with the world around you, you may not enjoy discovering that you have, in fact, been doing battle with yourself. You will fight this knowledge. You will see terrifying visions. Hell will become a real place. If, however, you have loved life, if you have learned to remain open to it, then death is a liberation, a moment in which you recognize that there is no end to life. You are one with it in all its finite and infinite manifestations.” (Rubin, 1990, p. 190-191)

This, of course, precisely traces the course of Singer’s painful struggle and eventual realization in the film – and it also provides a good model for understanding actual cases like Storm’s, to which we now return. When we come to examine Storm’s resistance to the experience, we find that there were several strands all uniting to intensify his adamantine stance. At the time, he was, as he later conceded, a materialist and atheist with a profound conviction that nothing survives death. His continued sense of personal (and embodied) existence was a great ontological shock to him, and itself caused him enormous distress and confusion. Moreover, he had been suffering from excruciating pain for many hours and only his inability to kill himself prevented his suicide. American doctors later told Storm that his condition is normally fatal in five hours. Storm remained conscious and fought to stay alive for nine hours before he had his NDE, and survived until the evening of that same day before finally being operated upon (Corneille, 1989). Thus, a combination of extreme and unrelieved pain for many hours probably carried over into the beginnings of his NDE when his existential perplexities and denial only added to his distress. Storm certainly fits the picture Rubin describes of an embattled and tortured man, afraid of death, who finds that demons are tearing away his flesh.

Of course, Storm, like Rubin’s fictional Singer, eventually submitted to forces greater than his own ego and allowed the onrushing light, previously walled off by his own fear and resistance, to penetrate into and pervade his conscious being. When I asked Storm to reflect on the meaning of his own experience, and especially what enabled him to find his way to the light, he gave a most insightful reply:

“Psychologically I believe that I was unable to respond to the ‘Light’ (whether from within or without) because of my materialistic and self-centered world view. How is this form of narcissism eliminated so that one can have a transformative spiritual [experience]? It was necessary for me to be destroyed (ego obstruction) so that I could be reborn.” (H. Storm, personal communication, August 21, 1991)

In the same letter, Storm also commented on his experience from another interpretative angle which I should at least mention here. Many readers will have already realized that experiences like Storm’s, and Singer’s for that matter, have many elements of the classic form of the hero’s journey (Campbell, 1968) in which a descent is made into the underworld where menacing monsters and many life-threatening trials must be encountered and overcome before the hero can re-emerge, transformed, into the world of ordinary experience. This is also, of course, the shaman’s initiatory experience, with its motifs of trial by ordeal and bodily dismemberment (Kalweit, 1988; Walsh, 1990). On these comparisons, Storm appropriately observed,

“If you are familiar with Joseph Campbell’s ‘the hero’s journey,’ you will notice an extraordinary coincidence between my story and the archetypal myth. Or to put it simply, the ordeal precedes the reward. The ordeal in my out-of-body experience is consistent with traditional stories of seduction and torment by the ‘damned’ or demonics.” (H. Storm, personal communication, 1991)

These comparisons are not directly related to our testable hypotheses concerning these frightening NDEs, but they do help to give us a larger context in which to understand their meaning. They also allow us to appreciate from still another perspective why we should expect to find terror giving way to transcendent realization if the experience continues long enough.

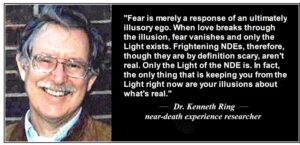

Finally, to round out these considerations on both “inverted” and hellish NDEs, I would like to offer an integrative theoretical approach that is based, loosely, on the teachings found in A Course in Miracles (1975). Although not directly testable as such, this framework is the most satisfactory – and simple – that I have yet come across as a means of understanding both positive and frightening NDEs. It also helps clarify something that hasn’t yet been apparent in my discussion of these experiences, namely, why classic, radiant NDEs can be said to be “real” in a way that frightening experiences cannot.

According to the Course, what’s real – and the only thing that’s real is what NDErs call “the Light,” that is, that realm of total love, complete acceptance, and universal knowledge whose energetic source and essence is what most people would feel comfortable calling “God.”

What’s illusion, on the other hand, is your idea of yourself, your ego. The Course further asserts that the ego is rooted in fear and the illusion that it is separate (from God, the Light). Naturally, to most of us, our ego seems real enough, just as our body seems solid, but, on analysis, it can be shown to be merely a conditioned construction of mental habits, an interconnected tissue of thoughts, with no intrinsic reality of its own. From this point of view, you – as a separate, independent ego – don’t really exist.

Thus we have two distinctly different realms:

God = Love = Reality itself

Ego = Fear = Illusion

Now, relating all this to the NDE, we can begin to see some important implications for frightening encounters – and their transformation. If, upon having an NDE, you are strongly identified with your ego and sufficiently attached to it that you cling to it like a drowning man might clutch a raft, you will naturally bring a great deal of fear into your experience (since the ego is predicated on fear). One is simply afraid “to go gently into that good night” since one’s ego is really all one has to hold on to. Such an individual’s emotional state will then tend to generate images consonant with that fear, which will only cause it to strengthen. The person will therefore continue to feel deeply menaced, as he or she is indeed threatened with extinction – as a separate ego. (The ego, of course, cannot recognize its own illusory nature; it’s part of the illusion.)

If, however, the person begins to let go, or simply surrenders to the Light, what happens? Obviously, one then becomes permeated by the Light – Reality itself. The ego is at least temporarily revealed to be an empty illusion whose function has only been to keep one screened off from the unconditioned splendor of one’s being, which is not different from but in reality an aspect of the Light itself.

According to A Course in Miracles, then, it comes down to this: If you are still clinging to your little island of make-believe, your ego, when you enter into death, you will experience its own fear, perhaps to the point of terror. If you can let go, however, just as Rubin has argued, you will find yourself one with the Infinite Light of life. Most readers will now appreciate here the appositeness of the familiar biblical phrase, “perfect love casts out fear” (1 John 4:18). Love and fear are incompatible states and are associated with two different and independent systems entirely. Love, in the sense the Course uses the term, and in the way most NDErs do, is an aspect of Reality itself. Fear is merely a response of an ultimately illusory ego. When love breaks through the illusion, fear vanishes and only the Light exists. Frightening NDEs, therefore, though they are by definition scary, aren’t real. Only the Light of the NDE is. In fact, the only thing that is keeping you from the Light right now are your illusions about what’s real.

6. Experiences of a “Meaningless Void”

When we come to the third and last type of frightening experience that Greyson and Bush delineated, we find ourselves in a very different realm from anything we have considered so far. Here the individual quickly is drawn into a meaningless void where he or she may be mocked and experience life not only as a cruel joke, but ultimately as an illusion. This situation is naturally perceived as intolerable, and the individual will struggle to prove that he or she does exist and that life does have meaning – but to no avail. In contrast to radiant NDEs in which time is absent, here the experiencer feels condemned to everlasting time in a meaningless universe. Greyson and Bush also pointed out that these experiences do not resolve themselves into positive ones in the way the previous types we have considered sometimes do.

A single extended example provided by Greyson and Bush may serve as a prototype here for this variety of frightening NDE. A twenty eight-year-old woman, when giving birth to her second child, after hours of labor found herself in a frame of mind she described as “fearful, depressed and panicky.” During the previous seven hours of labor, three pitocin drips had been started, and finally she was given nitrous oxide. She struggled against the mask, but was restrained and eventually went under the anesthetic. She recalled travelling rapidly upward into darkness, “rocketing through space like an astronaut without a capsule,” as she graphically put it (Greyson and Bush, 1992, p. 102). She then saw a small group of black and white circles, which were alternating in color and clicking as they did so. They jeered at the woman in a mocking and mechanistic fashion, and their message was, “Your life never existed. Your family never existed. You were allowed to imagine it…. It was never there…. That’s the joke – it was all a joke” (p. 102).

The woman then proceeded to argue with these voices, protesting that she did exist, and that her family did, too, but the jeering continued and the woman’s despair mounted. “This utter emptiness just went on and on, and they kept on clicking … The grief was just wrenching … Time was forever, endless rather than all at once. The remembering of events had no sense of a life review, but of trying to prove existence, that existence existed. Yes, it was more than real: absolute reality. There’s a cosmic terror we have never addressed” (p. 102).

In commenting on experiences of this kind, Greyson and Bush casually mentioned that “the majority of our cases … occurred during childbirth under anesthesia” (p. 104). This finding, I think, may be a vastly important clue to the mystery of these experiences and deserves to be explored more fully in relation to other anesthetic and drug induced experiences.

For example, Michael Sabom (1982), in his discussion of surgical NDEs, mentioned the work of another physician, Richard Blacher (1975), who had reported that patients who briefly awake under anesthesia only to find themselves paralyzed displayed a characteristic syndrome following their surgery consisting of “(1) repetitive nightmares, (2) generalized irritability and anxiety, (3) a preoccupation with death, and (4) difficulty … in discussing their symptoms, lest they be thought insane” (Sabom, 1982, p. 79). Sabom then went on to mention other cases of this kind, vouched for by other physicians, and concluded his commentary by quoting a letter from a physician who himself, as a patient, had had one of these anesthetically-induced episodes:

“Nearly everyone has had a bad dream of trying to run away from some form of danger, but being unable to move. The dream usually ends with the sleeper waking. Though I was not asleep [during surgery] I endured the same terror, but the ‘dream’ would not end. The sense of helplessness seemed to go on forever.” (Sabom, 1982, p. 79)

In these remarks concerning inadequately anesthetized patients, Sabom gave us some reason to think that at least some of the elements of this third type of frightening NDE may be attributable to the patient’s response to the anesthetic itself.

And there is more evidence to support this claim. Ketamine, the dissociative anesthetic I mentioned previously in connection with Kungurtsev’s work (1991) with chronic alcoholics, is a rapidly acting agent that produces an anesthetic state characterized by deep analgesia, though its physical side effects sometimes include hypertension and tachycardia (Martinez, Achauer, and Dobkin de Rios, 1985). Ketamine has seen widespread use in surgery, including obstetrics (Little, Chang, Chucot, Dill, Enrile, Glazko, Jassani, Kretchmer, and Sweet, 1972; Martinez, Achauer, and Dobkin de Rios, 1985).

Although, as we have seen, ketamine, at subanesthetic levels and with proper preparation of patients, can sometimes induce experiences that reproduce many of the essential features of transcendent NDEs, its use in conventional surgery has not been without problems. Specifically, what are called “emergence reactions” – confused and frightening sensations and hallucinations – are known to occur, sometimes in as many as one-third of the patients who receive it (Sklar, Zukin, and Reilly, 1981; White, Ham, Way, and Trevor, 1980; White, Way, and Trevor, 1982). Depersonalization is also apparently commonly reported (Collier, 1972). Finally – and significantly, in view of Greyson and Bush’s remark about the predominance of anesthetically-related childbirth cases among this kind of frightening NDE – it is known that such reactions are more likely to occur in women (White, Way, and Trevor, 1982) and that, specifically, they are fairly common in women undergoing childbirth (Little, Chang, Chucot, Dill, Enrile, Glazko, Jassani, Kretchmer, and Sweet, 1972).

To see how closely such ketamine-induced experiences may sometimes parallel this variety of NDE, permit me to describe one of my own sessions with this agent. Some years ago, I was asked by an oncologist to take part in a pilot study he was then conducting to determine whether ketamine could be used to induce NDEs in terminally ill patients. His thinking was that, if this could be demonstrated, the use of ketamine with such patients might be justified on the grounds of its easing their fear of death. Although I have never had an NDE, the physician felt that because of my research on the subject I would be a good candidate for his preliminary research.

With a mixture of natural curiosity and some misgivings, I agreed. I was given a drip-injection so that titration could be performed. This enabled the physician to gauge my reaction to gradual increases of ketamine. I was asked to speak, as long as I was able, into a tape recorder so that my subjective experiences to the drug could also be assessed at the time and not just retrospectively.

At the outset, the experience, though very strange, was not unpleasant, but I eventually reached a point where I became aware that I had lost all connection with, and belief in, life as I had previously understood it. I found myself in a soulless and totally mechanical universe, devoid of meaning. I remember I had the distinct and undeniable realization that human beings were nothing more than images projected onto a screen who had mistakenly come to identify with those images and had therefore naturally come to believe that they and other humans were real. But they were not – that was mere delusion. They were, in fact, no more real than dream figures. Furthermore, there seemed to be no one actually running the projector that produced those images. It was a motion picture without a director, and without a plot. I can still recall vividly my reaction of metaphysical horror, not just to my perception of these images, but to my unshakable insight that I was seeing into the stark and unutterably terrifying reality of the human situation.

When the ketamine wore off, I was still unable to dismiss what I had seen and experienced and was overcome by existential anguish. I remember clutching the elbow of the physician’s assistant, both to take comfort in the sheer tactual sensation it provided, but also to try to reassure myself that the human body was real and substantial, and that I was, too.

Such existentialist nightmare visions, of course, are by no means unique to ketamine. Other drugs can also induce them, including lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). One of the pioneers of LSD research, beginning in the mid-’50s in the former Czechoslovakia, is Stanislav Grof (1975, 1988), the well-known psychiatrist. Grof, for nearly two decades, made systematic observations of the effects of psychedelic agents as adjuncts to psychotherapy, and has elaborated a widely endorsed model among transpersonally-oriented practitioners and researchers in terms of which to understand the variety of experiences brought about by these substances. Particularly pertinent here is that portion of his model concerned with what he calls “perinatal experiences,” that is, experiences that appear, in part, to mimic or reproduce aspects of the birth process in both their biological and symbolic aspects. It is not necessary, however, to accept Grof’s own interpretation of these experiences in order to appreciate their relevance to the type of NDE under consideration here.

Grof divided these perinatal experiences into four distinct clusters, which he called “Basic Perinatal Matrices” (BPMs). It is the second of these clusters, BPM II, that concerns us here. Of this matrix Grof wrote:

“For a person experientially tuned in to the elements of BPM II, human life seems bereft of any meaning. Existence appears not only nonsensical but monstrous and absurd, and the search for any meaning in life futile, and, a priori, doomed to failure … Another typical category of visions related to this perinatal matrix involves the dehumanized, grotesque, and bizarre world of automata, robots, and mechanical gadgets, the atmosphere of human monstrosities and anomalies in circus sideshows, or of a meaningless “honky-tonk” or “cardboard” world … Another important dimension of [this matrix] is the feeling of pervading insanity; subjects typically feel that … they have gained the ultimate insight into the absurdity of the universe and will never be able to return to the merciful self-deception that is a necessary prerequisite for sanity … Agonizing feelings of separation, alienation, metaphysical loneliness, helplessness, hopelessness, inferiority and guilt are standard components of BPM II … Typically, this situation is absolutely unbearable, and at the same time, appears to be endless…. [Yet though] the individual trapped in [this] situation clearly sees that human existence is meaningless … [he] feels a desperate need to find meaning in life.” (Grof, 1975, p. 116-120)

An illustrative instance of these insights – and of the tormentingly vain attempt to deny them – in an actual case is provided by this account:

“At that point, I understood the existentialist philosophers and the authors of the Theater of the Absurd. THEY KNEW! Human life is absurd, monstruous, and utterly futile; it is a meaningless farce and a cruel joke played on humanity … It seemed essential to me to find some meaning in life to counteract this devastating insight; there had to be something! But the experience was mercilessly and systematically destroying all my efforts. Every image I was able to conjure up to demonstrate there was meaning in human life was immediately followed by its negation and ridicule … I felt caught in a vicious circle of unbearable emotional and physical suffering that would last forever. There was no way out of this nightmarish world. It seemed clear that not even death, spontaneous or by suicide, could save me from it.” (Grof, 1988, p. 19-20)

What, then, is the import of these anesthetic and drug-induced experiences for our understanding of this third category of NDE? Because of the commonalities I have demonstrated, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that such experiences – though highly real – are not true NDEs as such but are essentially emergence reactions to inadequate anesthesia, which may, as in the case furnished by Greyson and Bush, be further intensified by initial resistance and fear. Experiences with ketamine and LSD, outside of surgical contexts, can also induce such states, as we have seen, and Grof’s comprehensive model easily subsumes them. Parsimony suggests, then, that we might best understand this variety of experience as reflecting mainly the effects of these anesthetic and psychedelic agents on human consciousness.

This assumption also appears to dovetail nicely with the tentative observations Greyson and Bush offered concerning the long-term effects of these experiences. They suggested that these episodes may well leave the individual with a pervasive sense of emptiness and fatalistic despair and in a condition of “ontological fear (Greyson and Bush, 1992, pp. 104, 109).” Interestingly enough, Grof has found evidence of the same effects for persons whose psychedelic experiences remain unresolved and under the imprint of BPM II (Grof, 1975, p. 151).

Finally, let me summarize the testable hypotheses concerning this last variety of frightening experience that follow from my analysis. First, we would expect that a disproportionate number of these experiences would involve the use of anesthetics, and that possibly they would be more likely to be reported by women. Second, the long-term effects of these experiences, unless modified by later transcendental encounters, should prove to be quite different from, and more negative than, those typically associated with radiant NDEs.

7. Conclusion

This analysis I have offered of the three varieties of frightening NDEs that Greyson and Bush distinguished in their typology is scarcely more than a first step toward guiding future research on an important but neglected topic in near-death studies. The formulation that I have proposed, however, does at least have the advantage that it leads to a number of testable hypotheses that could be evaluated in subsequent investigations of frightening NDEs. Moreover, it also points to the possible relevance of other more encompassing perspectives, such as that drawn from A Course in Miracles, traditions of Eastern thought, the mythology of the hero’s quest, and Grof’s transpersonal model, in terms of which to understand the full range of NDEs generally.

Of course, I hold no expectations that the framework I have outlined here will be sufficient to explain all cases of frightening NDEs. Indeed, there have been some instances already reported in the literature (Irwin and Bramwell, 1988) that appear not to conform to my analysis. But this is not surprising since any given NDE is certainly multi-determined and obviously not all possible factors that may influence these experiences can be addressed by any one model. The question and it still needs to be answered by future research – is whether the ideas I have brought forward here will be useful both in stimulating further work on frightening NDEs and in helping us understand their dynamics and variations.

One last point on the ontological status of these frightening NDEs is in order. According to my analysis, the fear associated with these encounters is mediated by the human ego, which is ultimately an empty fiction. One might say, then, that frightening NDEs are themselves illusory phantasmagories thrown up by the ego in response to the threat of its own seeming imminent annihilation. These understandable and even terrifying distractions, however, will in time prove to be no match for the power of the Light, which is unconditional and, if I am right, an expression of Reality itself. Thus, it is the transcendent and not the frightening NDE that is, after all, a leaking through of ultimate reality. Frightening NDEs merely reflect the fact that hell is actually the experience of an illusory separative ego fighting a phantom battle.

8. References

Atwater, P.M.H. (1992). Is there a hell? Surprising observations about the near-death experience. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 10, 149-160.

Blacher, R.S. (1975). On awakening paralyzed during surgery – a syndrome of traumatic neurosis. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 234, 67-68.

Campbell, J. (1968). The hero with a thousand faces. New York, NY: World.

Collier, B.B. (1972). Ketamine and the conscious mind. Anaesthesia, 27, 120-134.

Corneille, A. (1989). Death: A beginning? Everybody’s News, October 27-November 9, pp. 4-5.

Course in Miracles, A. (1975). Tiburon, CA: Foundation for Inner Peace.

Gallup, G., Jr, and Proctor, W. (1982). Adventures in immortality: A look beyond the threshold of death. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Grey, M. (1975). Return from death: An exploration of the near-death experience. London, England: Arkana.

Greyson, B., and Bush, N.E. (1992). Distressing near-death experiences. Psychiatry, 55, 95-110.

Grof, S. (1975). Realms of the human unconscious. New York, NY: Viking.

Grof, S. (1988). The adventure of self-discovery. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Grof, S., and Halifax, J. (1977). The human encounter with death. New York, NY: Dutton.

Huxley, A. (1963). Heaven and hell. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Irwin, H.J., and Bramwell, B.A. (1988). The devil in heaven: A near-death experience with both positive and negative facets. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 7, 38-43.

Kalweit, H. (1988). Dreamtime and inner space. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Kungurtsev, I. (1991). “Death-rebirth” psychotherapy with ketamine. Bulletin of the Albert Hoffman Foundation, 2(4), 2-6.

Lindley, J.H., Bryan, S., and Conley, B. (1981). Near-death experiences in a Pacific Northwest American population: The Evergreen Study. Anabiosis: The Journal of Near-Death Studies, 1, 104-124.

Little, B., Chang, T., Chucot, L., Dill, W.A., Enrile, L.L., Glazko, A.J., Jassani, M., Kretchmer, H., and Sweet, A.Y. (1972). A study of ketamine as an obstetric anesthetic agent. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 113, 247-260.

Martinez, S., Achauer, B., and Dobkin de Rios, M. (1985). Ketamine use in a burn center: Hallucinogen or debridement facilitator? Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 17, 45-49.

Rawlings, M. (1978). Beyond death’s door. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Ring, K. (1980). Life at death: A scientific investigation of the near-death experience. New York, NY: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan.

Ring, K. (1984). The nature of personal identity in the near-death experience: Paul Brunton and the ancient tradition. Anabiosis: The Journal of Near-Death Studies, 4, 3-20.

Ring, K. (1988). Paradise is paradise: Reflections on psychedelic drugs, mystical experience, and the near-death experience. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 6, 138-148.

Rogo, D.S. (1984). Ketamine and the near-death experience. Anabiosis: The Journal of Near-Death Studies, 4, 87-96.

Rogo, D.S. (1989). The return from silence: A study of near-death experiences. Wellingborough, England: Aquarian Press.

Rubin, B.J. (1990). Jacob’s ladder. New York, NY: Applause.

Rubin, B.J. (Writer), Lyne, A. (Director), and Marshall, A. (Producer). (1991). Jacob’s ladder [Film]. Van Nuys, CA: Carolco.

Rubin, B.J. (Writer), Zucker, J. (Director), and Weinstein, L. (Producer). (1990). Ghost [Film]. Hollywood, CA: Paramount.

Sabom, M.B. (1979). [Review of Beyond death’s door]. Anabiosis [East Peoria], 1(3), 9.

Sabom, M.B. (1982). Recollections of death: A medical investigation. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Siegel, R.K., and Hirschman, A.E. (1984). Hashish near-death experiences. Anabiosis: The Journal of Near-Death Studies, 4, 69-86.

Sklar, G.S., Zukin, S.R., and Reilly, T.A. (1981). Adverse reactions to ketamine anaesthesia: Abolition by a psychological technique. Anaesthesia, 36, 183-187.

Walsh, R. (1990). The spirit of shamanism. Los Angeles, CA: Tarcher.

White, P.F., Ham, J., Way, W.L., and Trevor, A.J. (1980). Pharmacology of ketamine isomers in surgical patients. Anesthesiology, 52, 231-239.

White, P.F., Way, W.L., and Trevor, A.J. (1982). Ketamine – its pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Anesthesiology, 56, 119-136.