1. About The Author

Charles T. Tart, Ph.D. (www.aapsglobal.com/taste/ and www.paradigm-sys.com), is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology in Palo Alto, CA; Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of California at Davis; and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Noetic Science. Dr. Tart is a transpersonal psychologist and parapsychologist known for his psychological work on the nature of consciousness (particularly altered states of consciousness), as one of the founders of the field of transpersonal psychology, and for his research in scientific parapsychology. His first books, Altered States of Consciousness (1969) and Transpersonal Psychologies (1975), became widely used texts which were instrumental in allowing these areas to become part of modern psychology. Other books include: The Secret Science of the Soul (2017), Mind Science (2013), The End of Materialism (2009), States of Consciousness (2001), Living the Mindful Life (1994), and Waking Up (1986).

2. About This Article

This article is based on an Invited Address presented at the International Association for Near-Death Studies North American Conference, Oakland, CA, August 8-10, 1996. This article was published in the Journal of Near-Death Studies, 17(2) Winter 1998 C 1998 Human Sciences Press, Inc.73.

Reprint requests should be addressed to Dr. Tart at the Institute for Transpersonal Psychology, 744 San Antonio Road, Palo Alto, CA 94303.

3 Six Studies of Out-of-Body Experiences

By Charles Tart, Ph.D.

ABSTRACT: Because of confusion between science and scientism, many people react negatively to the idea of scientific investigation of near-death experiences (NDEs), but genuine science can contribute a great deal to understanding NDEs and helping experiencers integrate their experiences with everyday life. After noting how scientific investigation of certain parapsychological phenomena has established a wider world view that must take NDEs seriously, I review six studies of a basic component of the NDE, the out-of-body experience (OBE). Three of these studies found distinctive physiological correlates of OBEs in the two talented persons investigated, and one found strong evidence for veridical, paranormal perception of the OBE location. The studies using hypnosis to try to produce OBEs demonstrated the complexity of a simple model that a person’s mind is actually at an out-of-body location versus merely hallucinating being out, and require us to look at how even our perception of being in our bodies is actually a complex simulation, a biopsychological virtual reality.

Many people who hear about near-death experiences (NDEs) wish they could have that experience and that knowledge-without wanting to have the hard part of coming close to death, of course! As P. M. H. Atwater (1988) and others have documented, however, it is often not a simple matter of starting out “ordinary,” having an “extraordinary experience,” and then “living happily ever after.” Years of confusion, conflict, and struggle may be necessary as experiencers try to make sense of the NDE and its aftermaths, and to integrate this new understanding into their lives. Part of that struggle and integration takes place on transpersonal levels that are very difficult to put into words, part on a more ordinary level of questioning, changing, and expanding one’s world view. I shall use the term “transpersonal” rather than “spiritual,” as it has a more open connotation to it, whereas spiritual is usually associated with particular, codified belief systems.

As I have worked primarily as a scientist for the last 35 years, I will start by discriminating between genuine science and scientism, and then describe six studies of out-of-body experiences (OBEs) I have carried out and some of the conclusions I have come to that may be helpful in furthering understanding and integration.

4. Science and Scientism in the Modern World

We live in a world that has been miraculously transformed by science and technology. This is very good in some ways, not in others. One negative aspect of particular concern is that this material progress has been accompanied by a shift in our belief systems that is unhealthy in many ways, including a partial crushing of the human spirit by scientism. Note carefully that I said scientism, not science. I am a scientist, which I consider a noble calling that demands the best from me, and I am very much in favor of using genuine science to help our understanding in all areas of life, including the spiritual. Scientism, on the other hand, is a perversion of genuine science. Scientism in our time consists of a dogmatic commitment to a materialist philosophy that “explains away” the spiritual rather than actually examining it carefully and trying to understand it (Wellmuth, 1944). Since scientism never recognizes itself as a belief system, but always thinks of itself as true science, confusion between the two is pernicious.

Genuine science is a four part, continuing process that is always subject to questioning, expansion, and revision. It is a process that begins with a commitment to observe things as carefully and honestly as you can. Then you think about what your observations mean; that is, you devise theories and explanations, trying to be as logical as possible in the process. The next, third step is very important. Our minds are wonderfully clever, so clever that they can “make sense” out of almost anything with hindsight, that is, come up with some sort of plausible interpretation of why things happened the way we observed them to. But just because our theories and explanations seem brilliant and logical does not mean that we really understand the world we observed; we could have a wonderful post hoc rationalization. The third part of the genuine scientific process is a requirement that you keep logically working with, refining, and expanding your theories, your explanations, and then make predictions about new areas of reality that you have not yet observed. You have observed the results of conditions A, B, and C, for example, and come up with a satisfying explanation as to why they happened. Now develop your theory to predict what will happen under conditions D, E, and F, and then go out and set up those conditions and see what actually happens. If you have successfully predicted the outcomes, then you keep developing your theories. But if your predictions do not come true, your theories may need substantial revision or need to be thrown out altogether.

It does not matter how logical or brilliant or elegant or emotionally satisfying your theories are; they are always subject to this empirical test with new observations. Indeed, a theory that has no empirical, testable consequences may be philosophy or religion or personal belief, but it is not a scientific theory. Thus science has a built-in rule to help us overcome our normal human tendency to get emotionally committed to our beliefs. This is where scientism corrupts the genuine scientific process. Because people caught in scientism have an emotional attachment to a totally materialistic view of the world, they will not really look at data like NDEs that imply a spiritual, nonmaterial side to reality. They do not recognize that their belief that everything can be explained in purely material terms should be treated like any scientific theory; that is, it should be subject to continual test and modified or rejected when found wanting.

This requirement of continual testing, refinement, and expansion is part of the fourth process of genuine science, namely open, full, and honest communication about all the other three aspects. You share your observations, theories, and predictions so that colleagues can test and extend them. You as an individual may have blind spots and prejudices, but it is unlikely all your colleagues have the same ones; so that a gradual process of refinement, correction, and expansion takes place and scientific knowledge progresses. While this process is genuine science, it is also a quite sensible way of proceeding in most areas of life.

5. Inadequacy of Scientism in Dealing with NDEs

Now let us apply these thoughts about science and scientism to NDEs. Scientism, a dogmatic materialism masquerading as science, dismisses the NDE from the outset as something that cannot be what it seems to be, namely, a mind or soul traveling outside the physical body, either in the physical world or in some nonphysical world. So the NDE is automatically dismissed as a hallucination or, more likely, as some kind of psychopathology. But what if we practice actual science and look, with a view as objective as possible, at experiences like the NDE without prejudging them as impossible?

First, there are the data from a hundred years of scientific parapsychological research that, using the best kind of scientific methodology, show us that we cannot simply dismiss the NDE out of hand as impossible. A world view that countenances such dismissal is ignorant, prejudiced, or both.

Hundreds of experiments have shown that the human mind can sometimes do things that are paraconceptual to our understanding of physical reality; that is, they make no sense given our current understanding of physics and reasonable extensions of it, but they happen anyway. They are empirical realities. The four major psychic phenomena, collectively referred to as psi phenomena, that are well established are telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition, and psychokinesis (PK). Sometimes a person can detect what is happening in another’s mind (telepathy), detect what is happening at a distance in the physical world when it is not currently known to another mind (clairvoyance), predict the future when in principle it is not predictable (precognition), or affect physical processes just by willing them to be changed (PK). The reality of these psi phenomena requires us to expand our world view from a world that is only material to one that also has mind as some kind of independent reality in itself, capable sometimes of doing things that transcend ordinary physical limits (Tart, 1977a). So if in an NDE a person feels outside her or his body, or claims to have acquired information about distant events, for example, it may be an illusion in a particular case, but you cannot scientifically say it must be illusion. You have to examine the actual experience, the data, not ignore it or prejudicially “explain it away” without really paying attention or being logical. Thus psi phenomena give us a wider view of reality that calls for a careful look at NDEs, rather than dismissal out of hand.

6. Out-of-Body Experiences: Definition

Since the beginning of my career, I have been fascinated by what used to be a very little known phenomenon, the out-of-body experience (OBE). While the term OBE is sometimes used rather sloppily, I defined more than two decades ago what I called the classical out-of-body experience, or d-OBE-the “discrete out-of-body experience.” This is the experience where subjects perceive themselves as experientially located at some other location than where they know their physical body to be. In addition, they generally feel that they are in their ordinary state of consciousness, so that the concepts of space, time, and location make sense. Further, there is a feeling of no contact with the physical body, a feeling of temporary disconnection from it.

An NDE, on the other hand, usually has, speaking in an oversimplified way, two major aspects. First is the locational component, the OBE component: you find yourself located somewhere outside your physical body. Second is the noetic and altered state of consciousness (ASC) component: you know things not knowable in ordinary ways and your state of consciousness functions in quite a different way as part of this knowing. I separate these components as they do not always go together. You can have an OBE while feeling that your consciousness remains in its ordinary mode or state of functioning. If right this minute, for example, your perceptions showed you that you were someplace else than where you know your body is, but your consciousness was functioning basically like it is right now, that is what a classic OBE feels like. The OBE also seems as real or “realer” than ordinary experience. Reality is more complex than this, but this distinction between “pure” OBEs and typical NDEs will be useful for our discussion.

7. Out-of-Body Experiences: First Study

I conducted my first parapsychological experiment in 1957 while I was still a sophomore at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, studying electrical engineering. It was an attempt to produce OBEs with the aid of hypnosis, inspired by several old articles, especially one by Hornell Hart (1953), a sociologist turned parapsychologist. I trained several fellow students to be moderately good hypnotic subjects and then guided them in individual hypnotic sessions, in which I suggested that the participant’s mind would leave his body and go to the basement of a house several miles away, a place in a suburb of Boston he had never physically been to, and then describe what he saw in that basement.

The target house was the home of two parapsychologists, Fraser Nicol and Betty Humphrey, who had deliberately arranged a very unusual collection of objects in a corner of the basement. I reasoned that if any one of the subjects gave a good description of these unusual objects, I would know his mind had been there while out-of-body. Note the implicit model I had of OBEs, that it was equivalent to moving your sense organs, especially your eyes, to a distant physical location; I will question this simple model below. I had also placed a capacitance relay beside the target location to detect and record any disturbance in the electrical properties of the space around the targets, hoping that my hypnotized OBE participants might physically perturb the properties of space while they traveled to the targets, providing further evidence that the mind could actually leave the body. I installed the capacitance relay before Nicol and Humphrey placed any target materials on the table: I did not want to know what the targets were, so that I could not inadvertently give away any cues about them.

While I would not call the experiment a failure-I learned a lot from it-it did not work out as planned. The capacitance relay device had to be abandoned, as it went on and off every time the house furnace did. My participants’ descriptions of the target had occasional resemblances to the target materials, but the similarities were much too vague for me to put any reliance upon them. A “side trip” by one of the participants who was asked to describe my home in New Jersey, which he had never been to, was similarly suggestive, but not sufficiently so to convince me his mind had indeed left his body and traveled south. I had not yet learned how essential objective ways of evaluating results in parapsychology were.

8. Out-of-Body Experiences: Second Study

My next study of OBEs in the mid-1960s happened synchronistically (Tart, 1981). While chatting about various things with a young woman who babysat for us, I found out that, ever since early childhood, it was an ordinary part of her sleep experience occasionally to feel she had awakened from sleep mentally, but was floating near the ceiling, looking down on her physical body. This experience was clearly different from her dreams and usually only lasted a few seconds. As a child, not knowing better, she thought this was a normal part of sleeping. After mentioning it once or twice as a teenager she found it was not normal and she ceased talking about it! She had never read anything about OBEs, as this was long before Raymond Moody‘s Life After Life (1975), and had no idea what to make of it. I was quite interested, as she said she still had the experience occasionally.

I told her there were two theories about OBEs, one that they were what they seemed to be, namely, the mind temporarily leaving the physical body, and the other that OBEs were just some sort of hallucination. I suggested she could tell the difference by writing the numbers one to ten on slips of paper, putting them in a box on a bedside table, randomly selecting one to turn up without looking at it before going to sleep and then, if she had an OBE during the night, looking at and memorizing the number and then checking the accuracy of her memory in the morning. I saw her a few weeks later and she reported that she had tried the experiment seven times. She was always right about the number, so it seemed to her that she was really “out” during these experiences.

Miss Z, as I called her in my primary report on our work (Tart, 1968), had interrupted her college work to earn needed funds and was moving from the area in a few weeks, but before she left I was able to have her spend four nights in my sleep research laboratory. Each night I recorded her electroencephalogram (EEG) in a typical fashion used in dream research that allowed me to distinguish waking, drowsiness, and the various stages of sleep: two channels, frontal-to-vertex and vertex-to-occipital on the right side of the head, recording continuously through the night on a Grass Model VII Polygraph at a speed of 10 millimeters per second. I measured eye movements with a flexible strain gauge taped over one eye and I also measured the electrical resistance of her skin using electrodes taped to her right palm and forearm. On two of the four nights I also measured heart rate and relative blood pressure with an optical plethysmograph on her finger.

To ascertain whether she was, in some sense, really “out” of her body during her OBEs, I used the following procedure:

Each laboratory night, after the subject was lying in bed, the physiological recordings were running satisfactorily, and she was ready to go to sleep, I went into my office down the hall, opened a table of random numbers at random, threw a coin onto the table as a means of random entry into the page, and copied off the first five digits immediately above where the coin landed. These were copied with a black marking pen, in figures approximately two inches high, onto a small piece of paper. Thus they were quite discrete visually. This five-digit random number constituted the parapsychological target for the evening. I then slipped it into an opaque folder, entered the subject’s room, and slipped the piece of paper onto the shelf without at any time exposing it to the subject. This now provided a target which would be clearly visible to anyone whose eyes were located approximately six and a half feet off the floor or higher, but was otherwise not visible to the subject.

The subject was instructed to sleep well, to try and have an [out-of-body] experience, and if she did so, to try to wake up immediately afterwards and tell me about it, so I could note on the polygraph records when it had occurred. She was also told that if she floated high enough to read the five-digit number she should memorize it and wake up immediately afterwards to tell me what it was. (Tart, 1968, p. 8)

Over her four laboratory nights, Miss Z reported three clear cut incidents of “floating” experiences, in which she felt that she might have partly gotten out of her body but the experience did not fully develop, and two full OBEs. My general impression of the physiological patterns accompanying her floating and full OBE experiences is that she was in no way near death. There were no major heart rate or blood pressure changes and no particular activity in the autonomic nervous system.

Furthermore, floating and full OBEs occurred in an EEG stage of poorly developed stage 1 sleep, mixed with transitory periods of brief wakefulness. Stage 1 normally accompanies the descent into sleep, the hypnagogic period, and later dreaming during the night, but these were not like those ordinary stage 1 periods because they were often dominated by alphoid activity, a distinctly slower version of the ordinary waking alpha rhythm, and there were no rapid eye movements (REMs) accompanying these stage 1 periods, as almost always happens in normal dreaming. As to what this poorly developed stage 1 with dominant alphoid and no REMs meant, that remains something of a mystery. I showed the recordings to one of the world’s leading authorities on sleep research, William Dement, and he agreed with me that it was a distinctive pattern, but we had no idea what it meant. But it has left an idea with me that I have never been able to follow up, but which might prove fruitful. If you could teach someone to produce a drowsy state and slowed alpha rhythms, for example, through biofeedback training, would such a psychological procedure then make it easier to have an OBE? Indeed I found a report of a sensory deprivation study that reported alphoid rhythms occurring and also reported some subjects feeling as if they had left their bodies (Heron, 1957). I wrote to the researcher asking if these two things were associated, but never received a reply; perhaps the question was too controversial.

On the first three laboratory nights Miss Z reported that in spite of occasionally being “out,” she had not been able to control her experiences enough to be in position to see the target number (which was different each night). On the fourth night, at 5:57 AM, there was a seven minute period of somewhat ambiguous EEG activity, sometimes looking like stage 1, sometimes like brief wakings. Then Miss Z awakened and called out over the intercom that the target number was 25132, which I wrote on the EEG recording. After she slept a few more minutes I woke her so she could go to work and she reported on the previous awakening that:

I woke up; it was stifling in the room. Awake for about five minutes. I kept waking up and drifting off, having floating feelings over and over. I needed to go higher because the number was lying down. Between 5:50 and 6:00 A.M. that did it. … I wanted to go read the number in the next room, but I couldn’t leave the room, open the door, or float through the door. … I couldn’t turn off the air conditioner! (Tart, 1968, p. 17)

The number 25132 was indeed the correct target number. I had learned something about designing experiments since my first OBE experiment and precise evaluation was possible here. The odds against guessing a 5-digit number by chance alone are 100,000 to 1, so this was a remarkable event! Note also that Miss Z had apparently expected me to have propped the target number up against the wall behind the shelf, but she correctly reported that it was lying flat.

Whenever striking parapsychological results occur, both skeptics and other parapsychologists worry that they might have been fraudulently produced, or happened through some normal sensory channel, for such things have happened historically. With the help of Arthur Hastings, who is a skilled amateur magician as well as a parapsychologist, I carefully inspected the laboratory later to see if there was any chance of this. We let our eyes dark adapt to see if there was any chance the number might be reflected in the plastic casing of the clock on the wall above the number, but nothing could be seen unless we shone a bright flashlight directly on the numbers. Unless Miss Z, unknown to us, had employed concealed apparatus to illuminate and/or inspect the target number, which we had no reason to suspect, there was no normal way that anyone lying in bed, and having only very limited movement due to the attached electrodes, could see it.

I was cautious in my original write-up of these results, however, writing that “Miss Z’s reading of the target number cannot be considered as providing conclusive evidence for a parapsychological effect” (Tart, 1968, p. 18). I thought I was just making a standard statement of caution, as no one experiment is ever absolutely conclusive about anything, but overzealous critics have pounced on this statement as saying that I did not think there were any parapsychological effects in this study. I have always thought that some form of ESP was the best explanation of the results.

The most interesting criticism I have repeatedly received when describing this study comes from believers, rather than skeptics. Someone usually asks me whether I knew what the target number was. When I reply that I did, the criticism is that perhaps Miss Z was not really out of her body, but was merely using telepathy to read the number from my mind! I admit, with pleasure, that this first study of this type was indeed too crude to rule out the counter explanation of “mere telepathy.”

As you can imagine, I was quite pleased with the outcome of this study. An unusual experience, the OBE, was accompanied by an unusual EEG pattern, and there was strong evidence that Miss Z was correctly able to perceive the world from her out-of-body location. I was also greatly pleased at demonstrating that an exotic phenomenon like the OBE could be studied in the laboratory and have light cast on it, and the publication of this study stimulated other parapsychologists to think about doing research along these lines. My only regret was that Miss Z moved away and I was never able to track her down and do further work while I had laboratory facilities available. People who can have an OBE almost on demand are, to put it mildly, very, very rare.

9. Out-of-Body Experiences: Third Study

Some of the most interesting studies I have been able to do on OBEs have been with my dear friend the late Robert A. Monroe, the author of the classic book Journeys Out of the Body (1971), as well as his subsequent Far Journeys (1985) and Ultimate Journey (1994). Monroe was an archetypally “normal” American businessman who was “drafted” quite involuntarily into the world of OBEs and psychic matters as a result of a series of strange “attacks” of “vibrations” in the late 1950s, culminating in a classic OBE. Bayard Stockton’s biography (1989) provided full background material on Monroe’s life. I quote his account of his first OBE:

Spring, 1958: If I thought I faced incongruities at this point, it was because I did not know what was yet to come. Some four weeks later, when the vibrations came again, I was duly cautious about attempting to move an arm or leg. It was late at night, and I was lying in bed before sleep. My wife had fallen asleep beside me. There was a surge that seemed to be in my head, and quickly the condition spread through my body. It all seemed the same. As I lay there trying to decide how to analyze the thing in another way, I just happened to think how nice it would be to take a glider up and fly the next afternoon (my hobby at that time). Without considering any consequences-not knowing there would be any-I thought of the pleasure it would bring.

After a moment, I became aware of something pressing against my shoulder. Half-curious, I reached back and up to feel what it was. My hand encountered a smooth wall. I moved my hand along the wall the length of my arm and it continued smooth and unbroken.

My senses fully alert, I tried to see in the dim light. It was a wall, and I was lying against it with my shoulder. I immediately reasoned that I had gone to sleep and fallen out of bed. (I had never done so before, but all sorts of strange things were happening, and falling out of bed was quite possible.)

Then I looked again. Something was wrong. This wall had no windows, no furniture against it, no doors. It was not a wall in my bedroom. Yet somehow it was familiar. Identification came instantly. It wasn’t a wall, it was the ceiling. I was floating against the ceiling, bouncing gently with any movement I made. I rolled in the air, startled, and looked down. There, in the dim light below me, was the bed. There were two figures lying in the bed. To the right was my wife. Beside her was someone else. Both seemed asleep.

This was a strange dream, I thought. I was curious. Whom would I dream to be in bed with my wife? I looked more closely, and the shock was intense. I was the someone on the bed!

My reaction was almost instantaneous. Here I was, there was my body. I was dying, this was death, and I wasn’t ready to die. Somehow, the vibrations were killing me. Desperately, like a diver, I swooped down to my body and dove in. I then felt the bed and the covers, and when I opened my eyes, I was looking at the room from the perspective of my bed.

What had happened? Had I truly almost died? My heart was beating rapidly, but not unusually so. I moved my arms and legs. Everything seemed normal. The vibrations had faded away. I got up and walked around the room, looked out the window, and smoked a cigarette. (Monroe, 1971, pp. 27-28)

Monroe consulted his doctor to see what was wrong, but his health was fine. Fortunately he eventually spoke to a psychologist friend who told him that yogis had experiences like this and he should explore them, rather than worry. He did not find this advice particularly reassuring, but he had no choice in the matter as the vibrations and subsequent OBEs continued to occur.

I met Monroe in the fall of 1965 when I took a research position at the University of Virginia Medical School in Charlottesville. He was having OBEs regularly by then, although he had not yet developed the HemiSync techniques he later used to train others. Monroe was as curious about the nature of OBEs as I was and also able and eager to question his own experiences, rather than be dogmatically swept up in them. He was fascinated by what I had found out in working with Miss Z. Did his own body show similar brain wave changes or any death-like changes? Could we test whether he was “really” at the OBE location, rather than just hallucinating it? While he had had some experiences of being at a distant location where he was able to confirm the events later, there were too many others where such confirmation was only partial or even negative, even thought the experiences felt perfectly real. Ibo, if there were distinctive physiological changes during an OBE, then if we could learn to produce these same changes in people we might have a way of helping them to have OBEs. Monroe was as curious about the answers to these questions as I was.

I was able to have Monroe come in for eight late night sessions (his OBEs usually began from sleep) from December 1965 to August 1966 at the hospital’s EEG laboratory while he tried to get out of his body. This laboratory was not really equipped for sleep work, so much of the time Monroe was not completely comfortable on the cot we brought in and was unable to have an OBE. On his eighth night, however, things got interesting. Here are Monroe’s notes, written the next morning.

After some time spent in attempting to ease ear electrode-discomfort, concentrated on ear to ‘numb’ it, with partial success. Then went into fractional relaxation technique again. Halfway through the second time around in the pattern the sense of warmth appeared, with full consciousness (or so it seemed) remaining. I decided to try the ‘roll-out’ method (i.e., start to turn over gently, just as if you were turning over in bed using the physical body). I started to feel as if I were turning, and at first thought I truly was moving the physical body. I felt myself roll off the edge of the cot, and braced for the fall to the floor. When I didn’t hit immediately, I knew that I had disassociated. I moved away from the physical and through a darkened area, then came upon two men and a woman. The ‘seeing’ wasn’t too good, but better as I came closer. The woman, tall, dark-haired, in her forties (?) was sitting on a loveseat or couch. Seated to the right of her was one man. In front of her, and to her left slightly was the second man. They all were strangers to me, and were in conversation which I could not hear. I tried to get their attention, but could not. Finally, I reached over, and pinched (very gently!) the woman on her left side just below the rib carriage. It seemed to get a reaction, but still no communication. I decided to return to the physical for orientation and start again.

Back into the physical was achieved simply, by thought of return. Opened physical eyes, all was fine, swallowed to wet my dry throat, closed my eyes, let the warmth surge up, then used the same roll-out technique. This time, I let myself float to the floor beside the cot. I fell slowly, and could feel myself passing through the various EEG wires on the way down. I touched the floor lightly, then could ‘see’ the light coming through the open doorway to the outer EEG rooms. Careful to keep ‘local,’ I went under the cot, keeping in slight touch with the floor, and floating in a horizontal position, fingertips touching the floor to keep in position. I went slowly through the doorway. I was looking for the technician. but could not find her. She was not in the room to the right (control console room), and I went out into the brightly lighted outer room. I looked in all directions, and suddenly, there she was. However, she was not alone. A man was with her, standing to her left as she faced me. I tried to attract her attention, and was almost immediately rewarded with a burst of warm joy and happiness that I had finally achieved the thing we had been working for. She was truly excited, and happily and excitedly embraced me. I responded, and only slight sexual overtones were present which I was about 90% able to disregard. After a moment, I pulled back, and gently put my hands on her face, one on each cheek, and thanked her for her help. However, there was no direct intelligent objective communication with her other than the above. None was tried, as I was too excited at finally achieving the disassociation-and staying ‘local.’

I then turned to the man, who was about her height, curly haired, some of which dropped over the side of his forehead. I tried to attract his attention, but was unable to do so. Again, reluctantly, I decided to pinch him gently, which I did. It did not evoke any response that I noticed. Feeling something calling for a return to the physical, I swung around and went through the door, and slipped easily back into the physical. Reason for discomfort: dry throat and throbbing ear.

After checking to see that the integration was complete, that I ‘felt’ normal in all parts of the body, I opened my eyes, sat up, and called to the technician. She came in, and I told her that I had made it finally, and that I had seen her, however, with a man. She replied that it was her husband. I asked if he was outside, and she replied that he was, that he came to stay with her during these late hours. I asked why I hadn’t seen him before, and she replied that it was ‘policy’ for no outsiders to see subjects or patients. I expressed the desire to meet him, to which she acceded.

The technician removed the electrodes, and I went outside with her and met her husband. He was about her height, curly haired, and after several conversational amenities, I left. I did not query the technician or her husband as to anything they saw, noticed, or felt. However, my impression was that he definitely was the man I had observed with her during the non-physical activity. My second impression was that she was not in the control console room when I visited them, but was in another room, standing up, with him. This may be hard to determine, if there is a first rule that the technician is supposed to always stay at the console. If she can be convinced that the truth is more important in this case, perhaps this second aspect can be validated. The only supporting evidence other than what might have appeared on the EEG lies in the presence of the husband, of which I was unaware prior to the experiment. This latter fact can be verified by the technician, I am sure. (Tart, 1967, pp. 254-255)

As with Miss Z, Monroe’s physiological changes were interesting but not medically exciting. He was not at all near death, just showing the relaxed body characteristics of sleep and relaxation. This fits the general pattern that emerged from many later studies that while being physiologically close to death may facilitate the occurrence of an NDE, it is not necessary for either NDEs or OBEs. As to exactly what was Monroe’s state during OBEs, there was some general similarity to Miss Z’s, in that both involved a stage 1 EEG pattern that was somewhat like, but not identical to, ordinary dreaming, but the two patterns, in the limited sampling of these two studies, were not identical. Monroe had some alphoid activity, but not the large amount Miss Z showed. He also showed REMs in his second OBE where he reported seeing a stranger with the technician. Too, in the all-night study we also did with Monroe to get a baseline of normal sleep, when he was not trying for OBEs, he showed a normal pattern, and did not call the stage 1 REM periods that occurred there OBEs. He sharply distinguished the states of consciousness of his dreams and his OBEs.

We must remember too that while there is a strong correlation between EEG stage 1 REM pattern and the psychological experience of dreaming, correlation is not causality or identity with the physiological state of stage 1. We can think of stage 1 REM as a physiological state that has evolved during the sleep of mammals. In humans the psychological activity of dreaming can use this physiological pattern to manifest itself readily, although psychological states very like dreaming may sometimes occur in other physiological conditions. Too, the lucid dream, a dream state in which consciousness “wakes up” and feels in full possession of its waking faculties, also occurs in the physiological state of stage 1 REM (LaBerge, 1991). Perhaps an OBE is also facilitated in this same physiological state.

Was Monroe really “out” when he saw the technician away from her machine and speaking with a strange man? In her notes, my technician reported:

… In the second sleep the patient saw me [the tech] and he said I had a visitor, which I did. However, it is possible that Mr. Monroe may have heard the visitor cough during his [cigarette] break between sleeps. Mr. Monroe states that he patted the visitor on the cheeks and tried to take his hand but that the visitor avoided. Mr. Monroe recalls that he left the cot, went under it and out the door into the recording room and then into the hallway…. Mr. Monroe did not see the number.

Thus we have only weak evidence that Monroe was actually “out” on this occasion, a result he found as unsatisfactory as I did.

I left the University of Virginia post after a year there to take up a new position at the University of California at Davis, so our work ended for the time being on a note both encouraging and frustrating. The scientific world had doubled its knowledge about EEG patterns during OBEs, since there were now two studies instead of one, but a common pattern had not emerged, and the parapsychological aspects of Monroe’s OBEs had not been confirmed in this study.

10. Out-of-Body Experiences: Fourth Study

Several months later, after moving to California, I wanted to have more data about whether Monroe was really “out” in his OBEs, so I decided to try an experiment in which my wife Judy and I would, for a short period, try to create a sort of “psychic beacon” by concentrating on him, to try to help Monroe have an OBE and travel to our home. If he could describe our home accurately, this would be good evidence for a psi component in his OBEs, because he had no idea what our new home was like. As in my first study using hypnosis to try to produce OBEs, I was hoping for a big effect that would be obvious evidence of ESP.

I telephoned Monroe and told him that we would try to guide him across the country to our home at some unspecified time during the night of the experiment. That was all I told him. That evening I randomly selected a time to begin concentrating; the only restriction I put on my choice was that it would be some time after I thought Monroe had been asleep for a while. The time turned out to be 11:00 PM California time, 2:00 AM where Monroe lived in Virginia. At 11:00, my wife and I began our concentration; but at 11:05, the telephone rang. We never get calls late at night, so this was rather surprising and disturbing, but we did not answer the phone, nor did we have an answering machine so we did not know who had called. We tried to continue concentrating and did so until 11:30 PM.

The following day, I telephoned Monroe and noncommittally told him that the results had been encouraging, but that I was not going to say anything more about it until he had mailed me his written account of what he had experienced. His account was as follows:

The evening passed uneventfully, and 1 finally got into bed about 1:40 am, still very much wide awake. The cat was lying in bed with me. After a long period of calming mind, a sense of warmth swept over body, no break in consciousness, no pre-sleep. Almost immediately felt something (or someone) rocking my body from side to side, then tugging at my feet! (Heard cat let out complaining yowl.) I recognized immediately that this had something to do with Charley’s experiment, and with full trust, did not feel my usual caution with strangers (!) The tugging at my legs continued, and I finally managed to separate one second body arm and hold it up, feeling around in the dark. After a moment, the tugging stopped and a hand took my wrist, first gently, then very, very firmly and pulled me out of the physical (body) easily. Still trusting, and a little excited, I expressed feeling to go to Charley, if that was where he (it) wanted to lead me. The answer came back affirmatively (although there was no sense of personality, very businesslike). With the hand around my wrist very firmly, I could feel a part of the arm belonging to the hand (slightly hairy, muscular male). But could not “see” who belonged to the arm. Also heard my name called. Then we started to move, with the familiar feeling of something like air rushing around my body. After a short trip (seemed around 5 seconds in duration), we stopped, and the hand released my wrist. There was complete silence and darkness. When I drifted down into what seemed to be a room…. (Tart, 1977a, pp. 190-191)

When Monroe finished his brief OBE he got out of bed to telephone me: it was 11:05 PM, our time. Thus he experienced a tug pulling him from his body within one or two minutes of the time we started concentrating. The portion of his account that I have omitted, on the other hand, his description of our home and what my wife and I were doing, was quite inaccurate. He perceived too many people in the room, and perceived my wife and me performing actions that we did not do. Looking at the description, I would conclude that nothing psychic had happened. Thinking about the precise timing, though, I cannot help but wonder whether one can have an OBE in which one is really “out” in some sense, yet have grossly mistaken (extrasensory) perceptions of the location one has gone to. Whether or not that was the case in this experiment, after years of researching how much perception is a semi-arbitrary construction, often badly distorted, even in our normal state (Tart 1986, 1994), I have no doubt that this is possible for OBEs. I will return to this question later.

11. Out-of-Body Experiences: Fifth Study

In 1968 I was able to do one further study with Monroe when he briefly visited California. I had a functioning sleep laboratory at the University of California at Davis, more comfortable than the University of Virginia EEG lab, and he spent an afternoon with me and my assistants (Tart, 1969). In the course of a two-hour session, Monroe had two brief OBEs, and reported awakening within a few seconds after each, allowing correlation of physiological recordings with the OBEs. EEG, eye movements, and peripheral blood flow (plethysmograph) were again recorded, and he was monitored via closed circuit TV for the first OBE. The television monitoring equipment was already set up for other purposes, and I had vague hopes of seeing something ghost-like emerge from Monroe’s body if he had an OBE; but nothing unusual was seen and we turned it off after the first reported OBE as Monroe felt uncomfortable being watched.

Monroe was asked to try to produce an OBE, then to travel into the equipment room where my assistants and I were, and to read a five-digit target number in that equipment room. In his first OBE, he reported finding himself in the hall connecting the rooms for a period of eight to ten seconds at most, but then being forced to return to his body because of breathing difficulties. In his second OBE, he reported trying to follow the EEG cable through the wall to the equipment room but, to his amazement, found himself outside the building and facing the wall of another building, still following a cable. He later recognized a courtyard on the inside of the building, which had a three story wall and was 180 degrees opposite the equipment room, as the place he had experienced himself. Although he had no memory of ever having seen this courtyard, it is possible that he could have seen it while in my office earlier in the afternoon. There was no cable in the courtyard, at least not on the surface, although there may have been buried electrical cables under the surface connecting the wings of the building, and there were some cables from the laboratory room to my office, going most of the way toward the courtyard. Again we have that frustrating pattern of my research with Monroe of no ESP results clear enough to be conclusive, but not results so clearly inaccurate that I would feel comfortable saying nothing at all happened.

The EEG prior to Monroe’s reported OBE may be classified roughly as a borderline or hypnagogic state, a stage 1 pattern containing instances of alphoid activity rhythm (indicative of drowsiness) and theta activity (a normal sleeping pattern, part of stage 1). This pattern persisted through the first OBE, but was accompanied by a sudden fall of systolic blood pressure lasting seven seconds, this being roughly equivalent to Monroe’s estimated length of his OBE. There was REM activity of an ambiguous nature during this period. The second OBE was reported after a period of EEG shifting between stage 1 and stage 2 sleep. This second OBE’s exact duration is unknown, but appears to have been accompanied by a similar stage 1 pattern, and only two instances of isolated REM activity near the end. No clear-cut cardiac changes were seen on the plethysmographic recording. Monroe reported having used a different technique for producing the OBE this second time.

In general, then, Monroe’s OBEs seem to occur in conjunction with a prolonged, deliberately produced hypnagogic state (stage 1 EEG). Such prolonged states are not normally seen in the laboratory. The preponderance of theta rhythms and the occasional slowed alpha show an intriguing parallel with EEG states reported for advanced Zen masters during meditation (Kasamatsu, 1966). Modern EEG feedback techniques have shown that subjects can learn to produce increased alpha rhythm, and to slow the frequency of their alpha rhythm. If I were still actively researching this area, I would try training people to produce theta and slowed alpha rhythms, controlled drowsiness, as it were, and see if this helped them have OBEs. This is the sort of thing that Monroe worked on developing with his HemiSync procedures at the Monroe Institute, which Monroe often conceptualized as putting the body to sleep while keeping the mind awake. While I have been very intrigued and impressed with some of these results, I have not followed them closely enough to give a professional analysis of them, though reports have been circulated privately (F. H. Atwater and J. Owens, personal communication, 1995).

12. Out-of-Body Experiences: Sixth Study

The final OBE study I carried out in 1970 was like the first one in 1957, an attempt to use hypnosis to produce OBEs, but on a much more sophisticated level. I had done hypnosis research for more than a decade by this time, especially investigating the use of posthypnotic suggestion to influence the content and process of nocturnal, stage 1-REM dreaming. I had a small group of highly selected and trained participants at the University of California at Davis (Tart and Dick, 1970), all in the upper 10% of hypnotic susceptibility. Besides being adept at having their nocturnal dreams influenced posthypnotically, they had explored deep hypnotic states and were quite comfortable in the laboratory.

About seven of the participants had individual hypnotic sessions where they reached very deep hypnotic states, confirmed by their self-reports of hypnotic depth (Tart, 1970, 1972a, 1979). They then received a suggestion that, while the hypnotist remained quiet for 10 minutes so as to not disturb them or keep them connected to his or her body, their consciousness would leave their physical body and cross the hall into a second, locked laboratory room where some special target materials were on a table. They were to observe these materials carefully; then they could wander about out of body at will for a while, then return and report on their OBE to the experimenter, one of my graduate student assistants.

All the participants reported vivid OBEs that seemed like real experiences to them. They included journeys to places they knew, like downtown Davis, that were vividly experienced, as well as vivid experiences of journeying to the target room. None of their reports of what they saw on the target table bore any clear resemblance to the targets. A formal analysis was not worth the trouble.

13. Conclusion

So what is an OBE? Does the mind or soul really leave the body and go somewhere else, “out,” or is the OBE just a special altered state of consciousness that is basically hallucinatory in nature? That is, is the feeling and conviction that you are elsewhere than your physical body’s location an illusion? After decades of reflection on the results of my own and others’ research (Alvarado, 1982a, 1982b, 1984, 1986, 1989; Blackmore, 1984, 1994; Gabbard and Twemlow, 1984; Gackenbach, 1991; Green, 1968; Grosso, 1976; Irwin, 1985, 1988; Krippner, 1994; McCreery and Claridge, 1995; Morris, 1974; Osis and McCormick, 1980; Osis and Mitchell, 1977; Palmer, 1994; Palmer and Vassar, 1974; Rogo, 1978; Stanford, 1987; Walsh, 1989), particularly in the light of my studies on the nature of consciousness and altered states, I have a more complex view of OBEs that includes both of these possibilities at different times and more.

I believe that in some OBEs, the mind may, at least partially, really be located elsewhere than the physical body; this may have been the case with Miss Z. At the opposite extreme, as with my virtuoso hypnotic subjects whose experience was vivid and perfectly real to them but whose perception of the target room was only illusory, I believe an OBE can be a simulation of being out of the body, with the mind as much “in” the physical body as it ever is. In between these two extremes, I believe we can have OBEs that are basically a simulation of being out, but which are informed by information gathered by ESP such that the simulation of the OBE location is accurate and veridical. This is a messy situation in some ways, especially because all three of these types of OBEs may seem experientially identical to the person having them, at least at rough levels of description. While I would prefer reality to fall into simple, clear cut categories, I have learned in life that reality is often complex.

Simulation of Reality

We all have a model, a theory, about the nature of consciousness and of the world, although it is usually implicit, so that we do not consciously know we hold a theory. The theory is that space and time are real and pretty much what they seem to be and that things have a definite location in time and space; that consciousness is “in” the head, and that from that spatial position we directly perceive the outside world through our physical senses. As a working model, this theory works quite well most of the time: if someone throws a rock toward you, for example, an automated part of this model that has been called the ecological self (Neisser, 1988) instantly calculates the trajectory of the rock, compares it to where you are, and makes you duck if the trajectory intersects your position. In terms of biological survival, it is usually quite useful to identify psychologically with this ecological self and give very high priority to protecting your physical body. Indeed, it is very difficult not to identify automatically with this ecological self process.

Looking at this in more detail, we now know, through decades of psychological and neurophysiological research, that this naive view of perception-that consciousness just perceives the external world in a straightforward way-is quite inadequate. Almost all perception is really a kind of rapid, implicit, and automated thinking, a set of judgments and analyses about what is happening and its relevance to you. When something moves in the periphery of your visual field, for example, you will generally actually see a threatening person ducking behind a tree, rather than experience an ambiguous movement in the unfocused part of your visual field, leading to a thought of “What might it be?,” leading to searches of memory for possible candidates that show some fit to the ambiguous perceptual data available, leading to a conclusion that a threatening person ducking behind a tree has a 45 percent chance of fitting the perceptual data while, for example, a branch blowing in the wind has only a 30 percent chance of fitting, and so on, so that it would probably be best to get ready for action. If it really was a threatening figure, the person who sees it that way instantly has a better chance of survival by reacting faster than the one who goes through a long sequential analysis process. It is as if there is a distinct evolutionary advantage for the organism that has instant readiness to fight or flee even at the price of some false alarms, compared to the organism that takes too long to get ready to flee or fight.

It is useful, therefore, to see our ordinary consciousness as a process that creates an ongoing, dynamic simulation of reality, a world model, an inner theater of the mind, a biopsychological virtual reality (Tart, 1991, 1993), “in” which consciousness dwells. The most obvious example of this process is the nocturnal dream. There we live in a complete world, set in dimensions of space and time, with actors, plots, and an environment. Indeed, most of the brain mechanisms that construct the dream world are probably by and large the same mechanisms that construct our waking world with the very important difference that in the waking state this world simulation process must constantly deal with sensory input in a way that protects us and furthers our ends. Thus I have defined the reality we ordinarily live in as consensus reality (Tart, 1973), to remind us that, even though we implicitly think we perceive reality as it is, it is actually a complex construction, strongly determined by the social consensus of our particular society about what is important and our own psychodynamics and conditioning.

Applying this perspective to the study of OBEs and NDEs, we should first realize that the ordinary feeling that we are “in” our bodies (usually our heads), is a construction, a world simulation, that happens to be the optimal way to ensure survival most of the time, but that it is not necessarily true in any ultimate sense. It is helpful to remember that, just as a person using a high quality computer generated virtual reality simulator forgets where his or her physical body actually is, and becomes experientially located “in” the computer-generated world, it might be that our “souls” are actually located on some other planet, but we are so immersed in the biopsychological virtual reality our brains generate, and to which we are telepathically and psychokinetically connected (Tart, 1993), that we think we are here in our bodies. This far-fetched analogy helps to remind us that the experience of where we are is not a simple matter of just perceiving reality as it is.

A Scientific Model of Mind That Opens to Noetic Knowledge

Those who have had OBEs and NDEs know, on some very deep level, that mind or soul is something more than your physical body. The automatic psychological identification of who you are with the physical body, with the simulation constructed by the ecological self, is a very useful working tool, but not the final answer. As I noted at the beginning of this paper, integrating this experiential knowledge with your everyday self in the everyday world is not always easy, especially when the dominant climate of scientism constantly tells you that your deeper knowledge is wrong and that you are crazy to take it seriously.

My small contribution toward integration is the message that, using the best of scientific method rather than scientism, looking factually at all the data rather than just what fits into a philosophy of physicalism, the facts of reality require a model or theory of who we are and what reality is that takes OBEs and NDEs and noetic knowledge seriously. You are not deluded or crazy to try to integrate your NDE knowledge with the rest of your life. You are engaged in a real and important process!

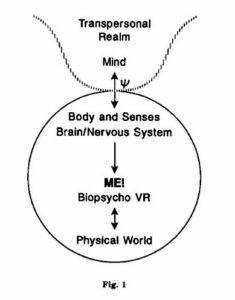

I can schematize my best scientific and personal understanding of our nature at this point with the diagram shown in Figure 1.

Being a product of my culture, at the top of the figure I have put the transpersonal or spiritual realm, shown as unbounded in extent. A part of that transpersonal realm, designated as mind in Figure 1, is in intimate relation with our particular body, brain, and nervous system. As I mentioned briefly above, although this mind is of a different nature from ordinary matter, psi phenomena like clairvoyance and PK are the means that link the transpersonal and the physical; that is, our mind has an intimate and ongoing relationship with our body, brain, and nervous system through what I have termed autoclairvoyance, where mind reads the physical state of the brain, and auto-PK, where mind uses psychokinesis to affect the operation of the physical brain.

The result of this interaction is the creation of a biopsychological virtual reality that I have labeled ME! in the figure, to stand for Mind Embodied, with the boldness of the type and the exclamation point added to remind us of the intensity of our identification with and attachment to ME! This ME! is a simulation of our ultimate, transpersonal nature, our physical nature, and the external physical world around us. We ordinarily live inside this simulation and take it for the direct perception of reality and our selves, but, as noted above, our ordinary self is indeed just a limited point of view, not the whole of reality. There is an immense amount of research needed to fill in the details of this general outline, but I think this conveys a useful general picture.

Summing Up

Let me close with some of the key points of this wider, higher-fidelity model. First, there is no doubt that the physics and chemistry of body, brain, and nervous system are important in affecting our experience. Further research on these areas is vitally important, especially if it is done without the traditional scientistic arrogance that physical findings automatically “explain away” psychological and experiential data.

Second, the findings of scientific parapsychology force us pragmatically to accept that mind can conduct information-gathering processes like telepathy, clairvoyance, and precognition, and can directly affect the physical world with PK-processes that cannot be reduced to physical explanations with current scientific knowledge or reasonable extensions of it. Therefore, it is vitally important to investigate what mind can do in terms of mind, rather wait for these processes to be “explained away” someday in terms of brain functioning, a form of faith that philosophers have aptly called promissory materialism, since it cannot be scientifically refuted. You can never prove that someday everything will not be explained in terms of a greatly advanced physics-or a greatly advanced knowledge of angels or dowsing or stock market movements. Recall that if there is no way of disproving an idea or theory, then you may like it or dislike it, believe it or disbelieve it, but it is not a scientific theory.

Third, the kind of research on the nature of mind called for above is vitally important, because most forms of scientism have a psychopathological effect on people by denying and invalidating their transpersonal experiences. This produces not just unnecessary individual suffering, but also attitudes of isolation and cynicism that worsen the state of the world.

Fourth, two of the most important kinds of transpersonal experiences people can have are OBEs and NDEs. They have major effects on experiencers’ attitudes toward life. Both seem to constitute a revelation of a more ultimate or higher understanding of who we really are. While this is important, it is also important to investigate these phenomena extensively, as they themselves may be, at least partially, simulations of even higher-order truths. The genuine scientific approach to them, then, is to take them seriously indeed, but, with humility and dedication: (a) try to get clearer data on their exact nature; (b) develop theories and understandings of them, both in our ordinary state and in appropriate altered states of consciousness, along the lines of state-specific sciences that I have proposed elsewhere (Tart, 1972b); (c) predict and test consequences of these theories; and (d) honestly and fully communicate all parts of this process of investigation, theorizing, and prediction. Genuine and open scientific inquiry has a lot to contribute to our understanding of our nature.

14. References

Alvarado, C. S. (1982a). Recent OBE detection studies: A review. Theta, 10(2), 35-38.

Alvarado, C. S. (1982b). ESP during out-of-body experiences: A review of experimental studies. Journal of Parapsychology, 46, 209-230.

Alvarado, C. S. (1984). Phenomenological aspects of out-of-body experiences: A report of three studies. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 78, 219-240.

Alvarado, C. S. (1986). ESP during spontaneous out-of-body experiences: A research and methodological note. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 53, 393-396.

Alvarado, C. S. (1989). Trends in the study of out-of-body experiences: An overview of developments since the nineteenth century. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 3, 27-42.

Atwater, P. M. H. (1988). Coming back to life: The after-effects of the near-death experience. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead.

Blackmore, S. J. (1984). A psychological theory of the out-of-body experience. Journal of Parapsychology, 48, 201-218.

Blackmore, S. J. (1994, August). Exploring cognition during out-of-body experiences. Paper presented at the Parapsychological Association 37th Annual Convention, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Gabbard, G. 0., and Twemlow, S. W. (1984). With the eyes of the mind: An empirical analysis of out-of-body states. New York, NY: Praeger.

Gackenbach, J. (1991). From lucid dreaming to pure consciousness: A conceptual framework for the OBE, UFO abduction, and NDE experiences. Lucidity, 10, 277308.

Green, C. (1968). Out-of-the-body experiences. Oxford, England: Institute of Psychophysical Research.

Grosso, M. (1976). Some varieties of out-of-body experience. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 70, 179-194.

Hart, H. (1953). Hypnosis as an aid in experimental ESP projection. Paper presented at the First International Conference of Parapsychological Studies, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Heron, W. (1957). The pathology of boredom. Scientific American, 196, 52-56.

Irwin, H. J. (1985). Flight of mind: A psychological study of the out-of-body experience. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Irwin, H. J. (1988). Out-of-body experiences and attitudes to life and death. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 82, 237-252.

Kasamatsu, A. H. T. (1966). An electroencephalographic study of the Zen meditation (Zazen). Folio Psychiatrica et Neurologica Japonica, 20, 315-336.

Krippner, S. (1994, August). A pilot study in ESP, dreams, and purported OBEs. Paper presented at the Parapsychological Association 37th Annual Convention, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

LaBerge, S. (1991). Physiological mechanisms of lucid dreaming. Lucidity, 10, 215-221.

McCreery, C., and Claridge, G. (1995). Out-of-the-body experiences and personality. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 60, 129-148.

Monroe, R. A. (1971). Journeys out of the body. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Monroe, R. A. (1985). Far journeys. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Monroe, R. A. (1994). Ultimate journey. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Moody, R. A. (1975). Life after life. Covington, GA: Mockingbird Books.

Morris, R. (1974). The use of detectors for out-of-body experiences. In W. G. Roll, R. L. Morris, and J. D. Morris (Eds.), Research in parapsychology, 1973 (pp. 114-116). Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Neisser, U. (1988). Five kinds of self-knowledge. Philosophical Psychology, 1, 35-39.

Osis, K, and McCormick, D. (1980). Kinetic effects at the ostensible location of an out-of-body projection during perceptual testing. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 74, 319-330.

Osis, K, and Mitchell, J. (1977). Physiological correlates of reported out-of-body experiences. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 49, 525-536.

Palmer, J. (1994, August). Out of the body in the lab: Testing the externalization hypothesis and psi-conduciveness. Paper presented at the Parapsychological Association 37th Annual Convention, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Palmer, J., and Vassar, C. (1974). ESP and out-of-the-body experiences: An exploratory study. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 68, 257-280.

Rogo, D. S. (1978). Mind beyond the body: The mystery of ESP projection. New York, NY: Penguin.

Stanford, R. G. (1987). The out-of-body experience as an imaginal journey: A study from the developmental perspective. In D. Weiner and R. Nelson (Eds.), Research in parapsychology, 1986 (pp. 111-115). Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Stockton, B. (1989). Catapult: The biography of Robert A Monroe. Norfolk, VA: Donning.

Tart, C. T. (1967). A second psychophysiological study of out-of-the-body experiences in a gifted subject. International Journal of Parapsychology, 9, 251-258.

Tart, C. T. (1968). A psychophysiological study of out-of-the-body experiences in a selected subject. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 62, 3-27.

Tart, C. T. (1969). A further psychophysiological study of out-of-the-body experiences in a gifted subject. Proceedings of the Parapsychological Association, 6, 43-44.

Tart, C. T. (1970). Self-report scales of hypnotic depth. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 18, 105-125.

Tart, C. T. (1972a). Measuring the depth of an altered state of consciousness, with particular reference to self-report scales of hypnotic depth. In E. Fromm and R. Shor (Eds.), Hypnosis: Research developments and perspectives (pp. 445-477). Chicago, IL: Aldine/Atherton.

Tart, C. T. (1972b). States of consciousness and state-specific sciences. Science, 176, 1203-1210.

Tart, C. T. (1973). States of consciousness. In L. Bourne and B. Ekstrand (Eds.), Human action: An introduction to psychology (pp. 247-279). New York, NY: Dryden Press.

Tart, C. T. (1977a). Psi: Scientific studies of the psychic realm. New York, NY: Dutton.

Tart, C. T. (1977b). Toward humanistic experimentation in parapsychology: A reply to Dr. Stanford’s review. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 71, 81-102.

Tart, C. T. (1979). Quick and convenient assessment of hypnotic depth: Self-report scales. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 21, 186-207.

Tart, C. T. (1981). Causality and synchronicity: Steps toward clarification. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 75, 121-141.

Tart, C. T. (1986). Waking up: Overcoming the obstacles to human potential. Boston, MA: New Science Library.

Tart, C. T. (1989). Open mind, discriminating mind: Reflections on human possibilities. San Francisco, CA: Harper and Row.

Tart, C. T. (1991). Multiple personality, altered states, and virtual reality: The world simulation process approach. Dissociation, 3, 222-233.

Tart, C. T. (1993). Mind embodied: Computer-generated virtual reality as a new, interactive dualism. In L. Rao (Ed.), Cultivating consciousness: Enhancing human potential, wellness and healing (pp. 123-137). Westport, C’: Praeger.

Tart, C. T. (1994). Living the mindful life. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Tart, C. T., and Dick, L. (1970). Conscious control of dreaming: I. The posthypnotic dream. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 76, 304-315.

Walsh, R. (1989). The shamanic journey: Experiences, origins, and analogues. Revision, 12(2), 25-32.

Wellmuth, J. (1944). The nature and origin of scientism. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press.